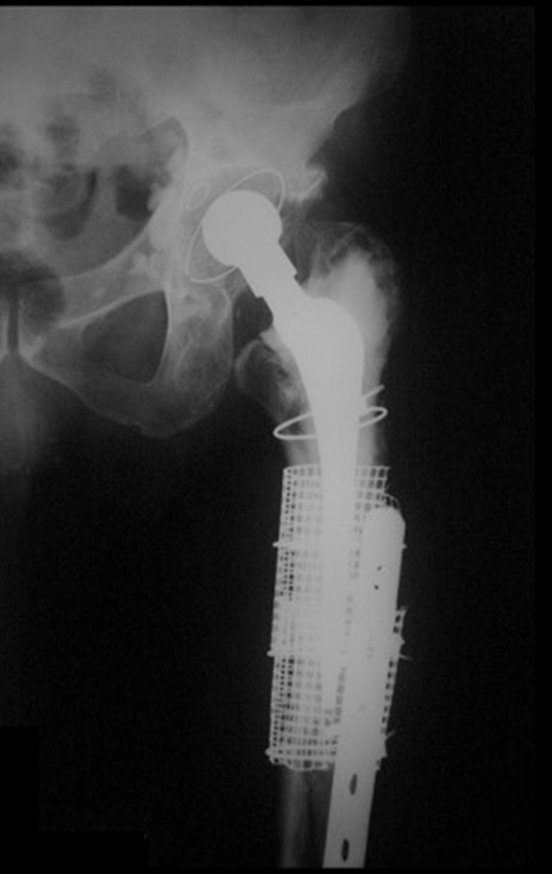

Technique for Revision of Infected Hip Prosthesis. A 52-year-old patient, with bilateral osteoarthritis of the hips, due to aseptic necrosis of the femoral heads, with more severe pain and disability on the left, underwent total hip arthroplasty E, figures 1 and 2.

Technique for revision of infected hip prosthesis – Arthrosis due to femoral head necrosis – Loosening and breakage of prosthesis, infection and fracture.

He later underwent surgery on the hip on the right side. During follow-up, the left femoral component became loose and, in February 2008, the stem broke. In May, the first revision was carried out, with a new prosthesis using a long neck and short stem, figures 3 and 4.

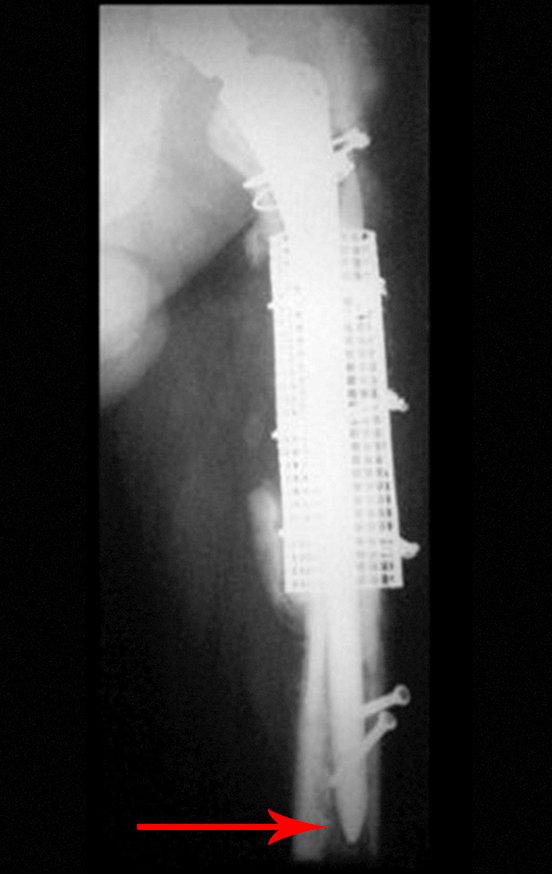

In February 2010, the long femoral stem was loosened, followed by a new revision with a plate, mesh, homologous graft and reinforced plate. Infection with active fistula and new releases, now with the patient presenting diabetes, figures 9 to 12.

From 2010 to 2014, the patient underwent surgical cleaning and systemic antibiotic therapy, under the supervision of an infectious disease specialist, in successive hospitalizations, aiming to achieve control of the infection for a two-stage revision.

In March 2014, we evaluated the patient and analyzed the case.

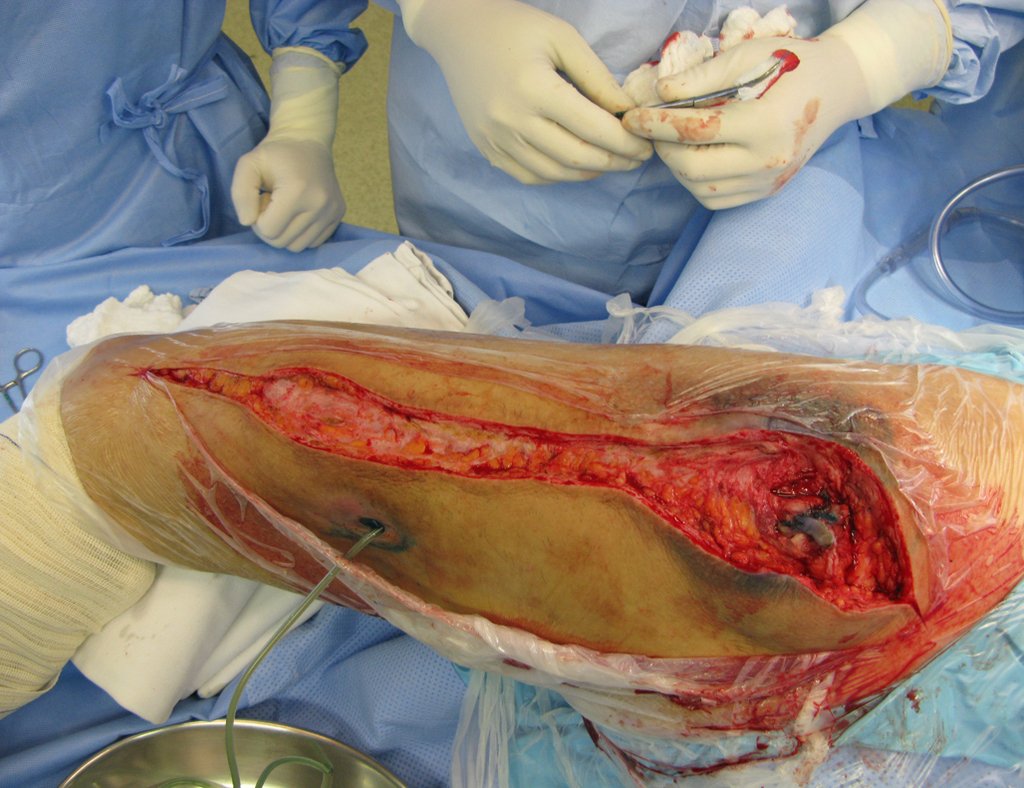

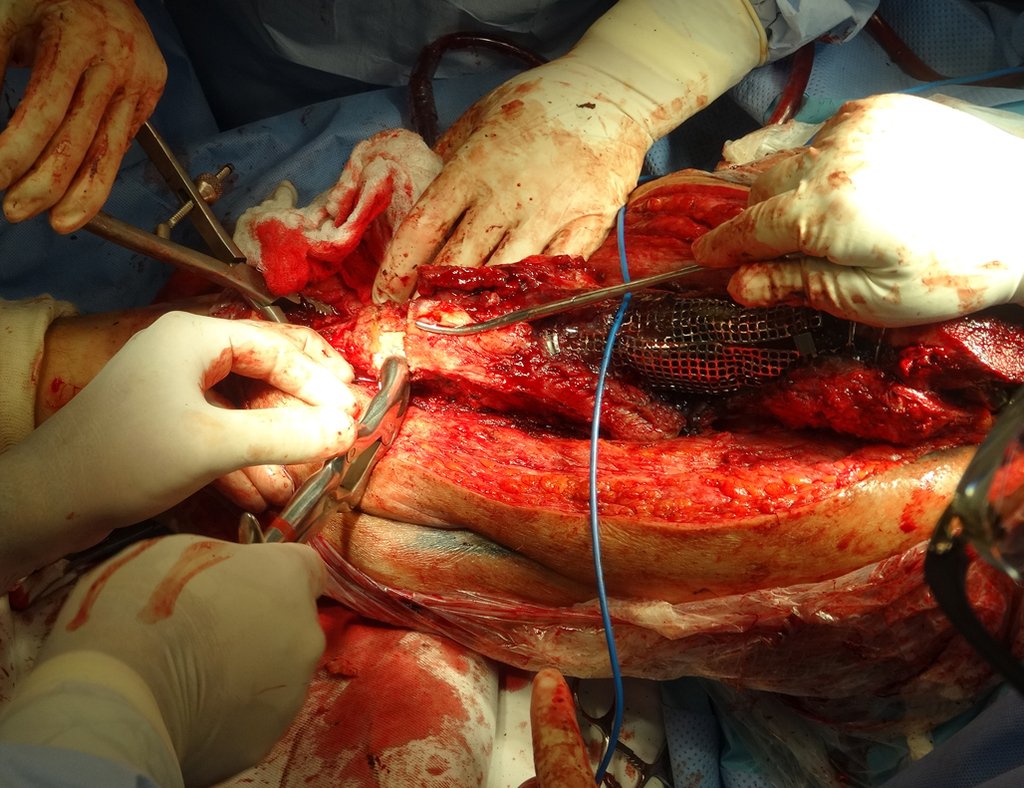

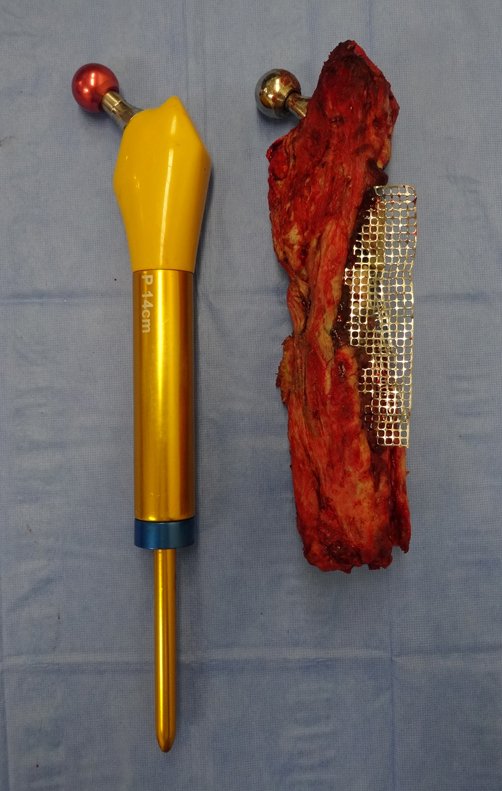

We recommend a single-stage revision, resecting the proximal segment en bloc, with prosthesis, plate, screws, mesh, wires, grafts, sequestrations and necrotic tissue, as if it were a neoplasm, and replacing it with a non-conventional polyethylene endoprosthesis.

This endoprosthesis is nothing more than a spacer, with the advantage of immediately filling the dead space and providing immediate function of the operated limb, figures 13 to 15.

Pre-operative radiographs of the revision in a surgical procedure, in April 2014, figures 19 to 128.

Revision surgery, April 8, 2014, figures 19 to 15.

After testing with the trial prosthesis and choosing the definitive modules, we proceed to cementing the endoprosthesis components, figures 42 to 53.

Around any endoprosthesis, fibrosis forms as a result of a foreign body reaction, resulting in a thick pseudo capsule, forming a case, which practically isolates this endoprosthesis from the body.

The muscles and tendons, which were initially inserted into the prosthesis with ethibond threads, end up definitively adhering to this pseudo capsule. This pseudo capsule has a lining of fluid-secreting synovial epithelium, which ends up covering the endoprosthesis. This reactional fibrosis of the pseudocapsule can reach 5 mm in thickness.

In revisions and even in surgeries with major muscle detachment, an increase in dead space may occur, resulting in the formation of excess synovial fluid, which increases the ¨case¨ that surrounds the prosthesis.

This increase in volume, associated with weakness of the abductor muscles, can facilitate hip dislocation.

On May 15, 2014, one month after surgery, the patient returned with an increase in thigh volume, no fever, no local heat, and signs of excess liquid content around the prosthesis.

This liquid, when in excess, must be drained. Sometimes more than one procedure is necessary.

It must be done with complete asepsis, using a large-caliber needle and emptying the contents as much as possible, figures 62 to 64.

A new drainage was performed by puncture, on 05/28/2015, after two weeks.

The patient was already able to walk with a walker and had no recurrence of the infection, figures 65 to 67.

Video 1: Patient walking with a walker two months after the review.

In June 2014, he performed a hyperflexion and internal rotation movement, while sitting on a low toilet, presenting hip dislocation. A closed reduction was performed and we reoriented again regarding the movements that facilitated the dislocation, as there was significant hypotrophy of the gluteus medius, which made stabilization of the prosthesis even more difficult.

A new episode of dislocation in July 2014, three months after surgery. We performed reduction maneuvers under radioscopy, without the need for sedation and obtained easy reduction and also easy displacement, confirming the inability to contain the reduced hip, due to the insufficiency of the abductor muscles and the femoral head that we used, which was small in size, figures 65 to 67 .

We had not changed the acetabulum in the previous surgery, maintaining a smaller head than the size of the previous acetabulum, which could also be contributing to the instability.

We decided on re-intervention with replacement of the acetabulum for a constricted module, also employing a larger head.

The patient evolved well, without complications, and was evaluated after one year, figures 83 to 86.

Video 2: Patient walking with trendelenburg, one year after the last surgery, acetabulum blocked, to overcome gluteus medius insufficiency.

Video 3: Patient walking without support, despite trendelemburg, after one year, on 07/27/2015.

To date, April 2, 2017, the patient is doing well, walking with a slight limp due to Trendelemburg, without any complications, three years after the last surgery.

Author: Prof. Dr. Pedro Péricles Ribeiro Baptista

Orthopedic Oncosurgery at the Dr. Arnaldo Vieira de Carvalho Cancer Institute

Office : Rua General Jardim, 846 – Cj 41 – Cep: 01223-010 Higienópolis São Paulo – SP

Phone: +55 11 3231-4638 Cell:+55 11 99863-5577 Email: drpprb@gmail.com