Introduction to the Study of Bone Tumors. The philosophy of this chapter is to present our experience and a form of objective reasoning. To treat it, you must first make the correct diagnosis.

We begin the approach to bone tumors seeking to convey “how I think” about musculoskeletal injuries.

Introduction to the Study of Bone Tumors

Firstly, we need to frame the condition we are evaluating within one of the five major chapters of Pathology:

1- CONGENITAL MALFORMATIONS

2- CIRCULATORY DISORDERS

3- DEGENERATIVE PROCESSES

4- INFLAMMATORY

5- NEOPLASTICS

If the case was classified within the neoplasms chapter, our objective is to establish the diagnosis so that we can institute treatment. It is essential to establish an accurate diagnosis.

To be diagnosed, it is necessary to know and learn the universe of tumors already described.

Are we, as medical students, not already aware of all musculoskeletal neoplasms?

We usually convey, in our classes, that our brain can store information randomly. However, if when we assimilate knowledge we try to do it in an orderly way, it will be “stored” in “folders”, these in “drawers” and we will have a “ file ” . This way we can retrieve the information more easily.

We will therefore help you build this file, organizing the “HD” .

Firstly, we need to remember that the neoplasm originates from a cell that already exists in our body. This cell, when reproducing, undergoes changes in its genetic code, due to different factors (radiation, viruses, mutations, translocations, etc.) and this then becomes the “ mother cell ” of the neoplasm.

As we already learned histology at the Faculty, we are knowledgeable about all possible neoplasms. We just need to add some concepts to safely name and classify all the tumors already described.

The term carcinoma was reserved for malignant neoplasms whose primitive cells originate from the ectodermal layer and sarcoma for those from the mesoderm.

If we take our thigh as an example and do an exercise, remembering all the cells that make it up, starting with the skin and going deeper into the subcutaneous tissue, muscles, etc., up to the bone marrow of the femur, we will have reviewed all the cells of the locomotor system. and therefore we will be able to name all musculoskeletal neoplasms.

Let’s do this exercise. Starting with the skin, we remember squamous cell carcinoma , basal cell carcinoma and melanoma . These neoplasms are most frequently treated by dermatologists and plastic surgeons and only rarely require the help of an orthopedist.

Below the skin, all structures are derived from the mesoderm and therefore we will add the suffix oma for benign lesions and sarcoma for malignant ones .

Therefore, below the skin we have the subcutaneous cellular tissue (fat) whose most representative cell is the lipocyte. If the lesion is made up of cells similar to the typical lipocyte, we will have a lipoma , consisting of disordered cells, with atypical mitoses, a liposarcoma . In this same subcutaneous tissue we have fibroblasts, fibrohistiocytes and consequently fibroma , fibrosarcoma , fibrohistiocytoma of low and high degree of malignancy.

Another structure that makes up our thigh are the striated muscles, (voluntary muscles), thus giving rise to rhabdomyosarcoma . Smooth muscles, found in the locomotor system, are located around the vessels and, although they are rare, we also find leiomyosarcoma .

Nervous tissue is represented here by the axons of peripheral nerves. These axons have a sheath, whose cells were described by Schwann, from which Schwannoma can originate .

In soft tissues, remembering, as derived from lymphatic tissue, lymphangioma and lymphangiosarcoma ; vascular tissue, hemangioma and angiosarcoma .

The bone is covered by the periosteum, whose function is to form bone tissue, in addition to protecting, innervating and nourishing. Trauma can lead to the formation of a sub-periosteal hematoma which, if mature, homogeneous ossification occurs, can be translated as a periosteoma (“osteoma”). Low-grade surface osteosarcoma known as paraosteal osteosarcoma (grade I) as well as high-grade osteosarcoma can be derived from this same bone surface .

In our exercise we now reach the medullary region of the bone. This region is made up of fat, which can then lead to intraosseous liposarcoma and red bone marrow, from which we can have all neoplasms of the ERS ( Reticulum Endothelial System ) such as plasma cell myeloma , lymphocytic lymphoma , Ewing’s sarcoma .

If we remember, deep in our memory, the histology of endochondral ossification, we will find several precursor cells. One of them is large (giant) made up of cells with several nuclei, responsible for bone resorption, the osteoclast and consequently we have osteoclastoma , better known as giant cell tumor ( GCT ). From the chondroblast the chondroblastoma ; osteoblast , osteoblastoma ; from the chondrocyte the chondroma , the chondrosarcoma ; and so on, we will be able to deduce all the neoplasms described. It will be enough to name them based on the knowledge of the normal cell, adding oma to the benign lesion and sarcoma to the malignant one.

We consider this form of introduction to be important, as this way we will be better helped to remember what we already know and arrive at the diagnosis.

The World Health Organization groups these injuries according to the tissue they try to reproduce, classifying them into:

I – Tumors that form bone tissue

Benign: Osteoma – Osteoid Osteoma – Osteoblastoma

Intermediate : Aggressive Osteoblastoma

Malignant : Central Osteosarcoma – Parosteal – Periosteal – High Grade

II – Cartilage-forming tumors

Benign : Chondroma (enchondroma) – Osteochondroma – Chondroblastoma – Chondromyxoid Fibroma

Malignant : Primary – Secondary – Juxtacortical – Mesenchymal – Dedifferentiated – Clear Cell Chondrosarcoma

III – Giant Cell Tumors (GCT) (Osteoclastoma)

IV – Bone Marrow Tumors

Malignant : Ewing Sarcoma – Lymphocytic Lymphoma – Plasmocyte Myeloma – PNET

V – Vascular Tumors

Benign : Hemangioma – Lymphangioma – Glomus tumor

Intermediate : Hemangioendothelioma – Hemangiopericytoma

Malignant : Angiosarcoma

VI – Connective Tissue Tumors

Benign : Fibroma – Lipoma – Fibrohistiocytoma

Malignant : Fibrosarcoma – Liposarcoma – Malignant fibrohistiocytoma – Leiomyosarcoma – Undifferentiated sarcoma

VII – Other tumors

Benign : Schwannoma – Neurofibroma

Malignant : Chordoma – Adamantinoma of the long bones

VIII – Metastatic Tumors in the Bone

Carcinomas: breast, prostate, lung, thyroid, kidney, neuroblastoma, melanoma, etc.

IX – Pseudotumor Lesions

Simple bone cyst (COS)

Aneurysmal bone cyst (AOC)

Juxta-articular bone cyst (intraosseous ganglion)

Metaphyseal fibrous defect (Non-ossifying fibroma)

Fibrous dysplasia

Eosinophilic granuloma

“Myositis ossificans”

Brown tumor of hyperparathyroidism

Intraosseous epidermoid cyst

Giant cell reparative granuloma

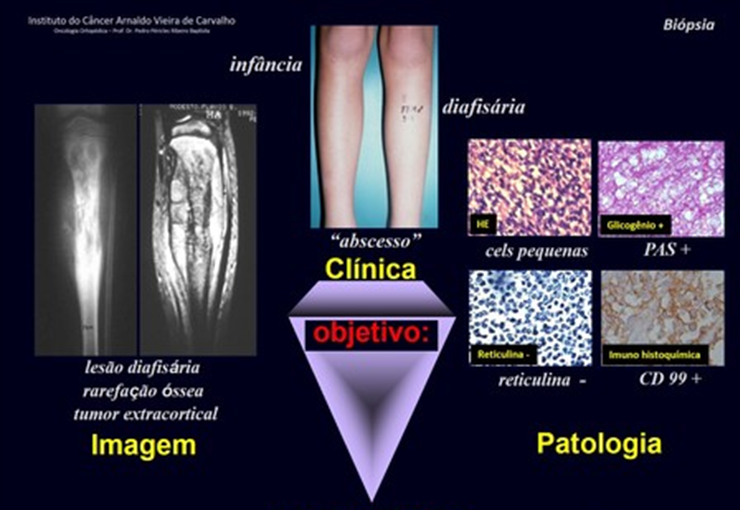

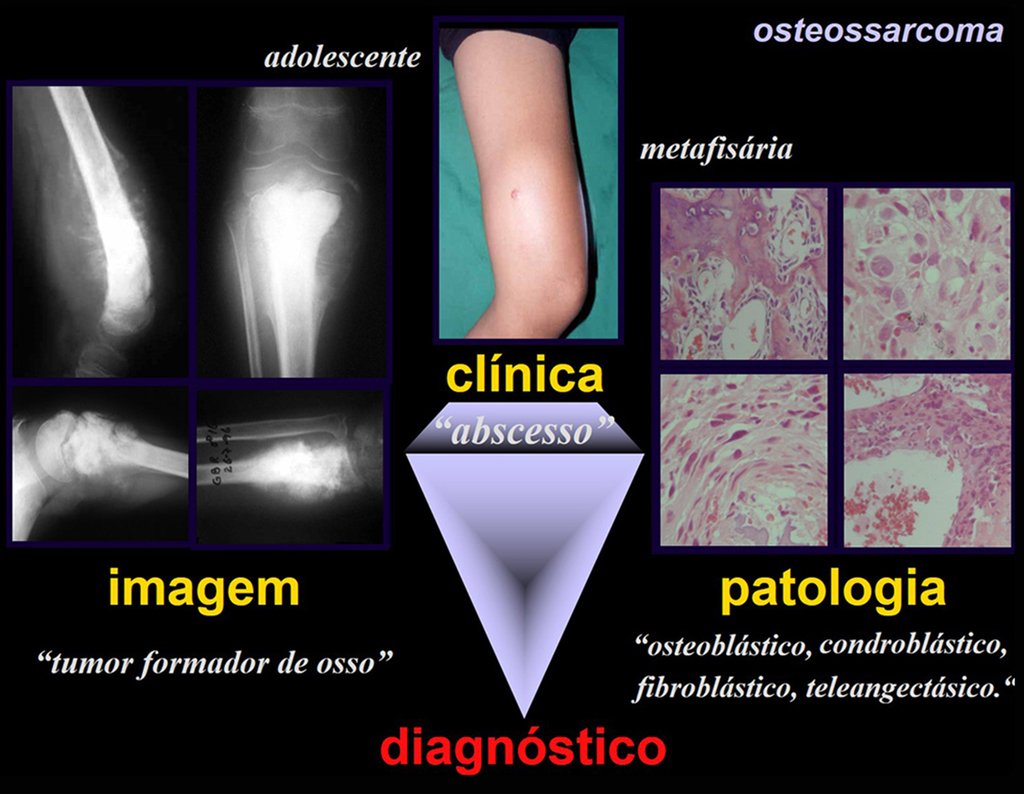

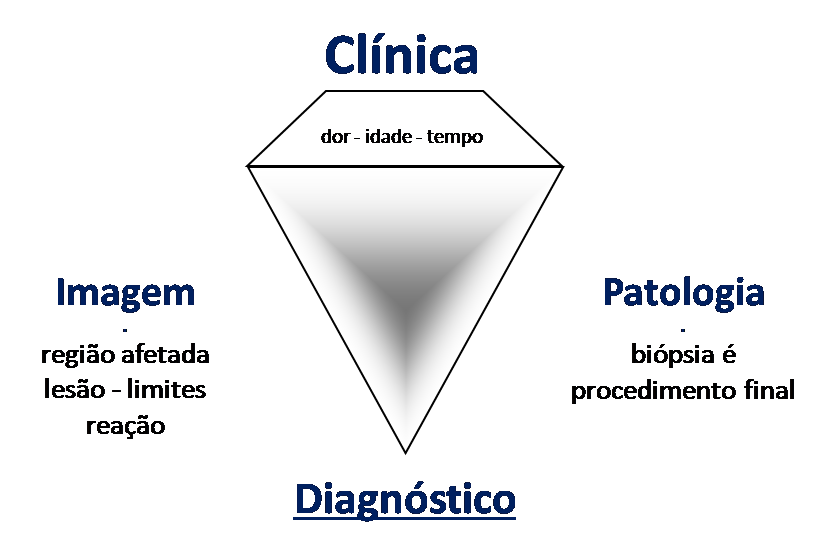

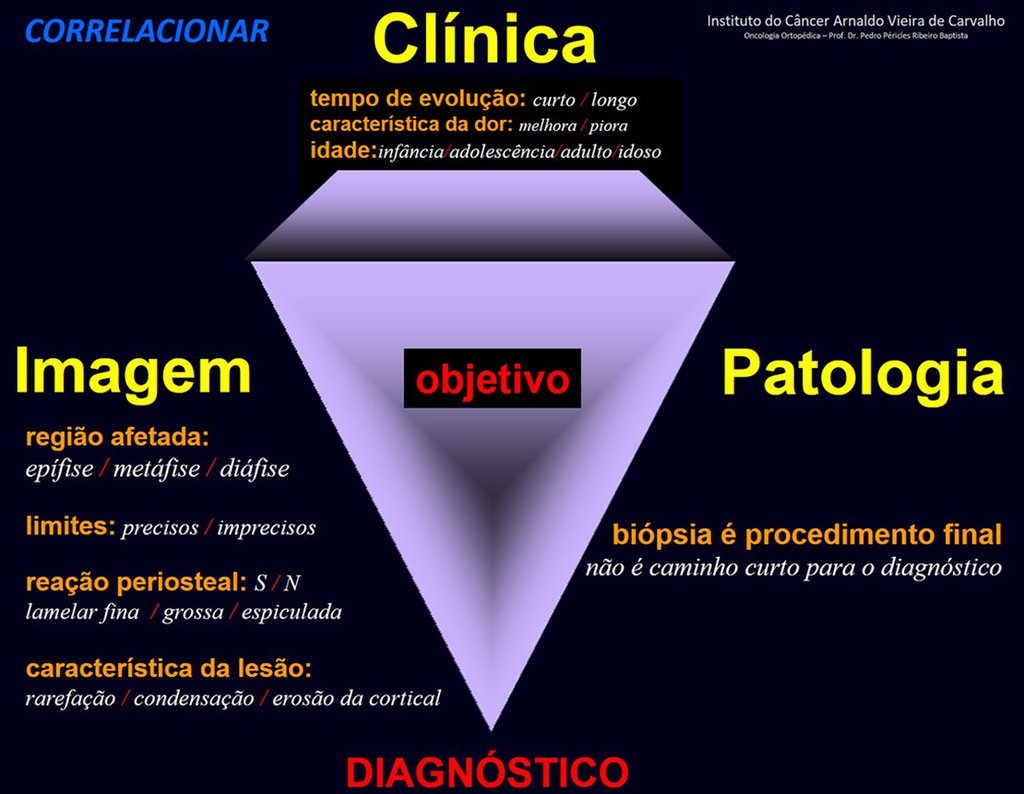

All of these lesions mentioned have clinical particularities , imaging characteristics , and histological aspects that need to be analyzed together to correlate each one of them.

This is fundamental, as we can have radiologically and/or histologically similar lesions but with different diagnoses.

Therefore, imaging studies and histology must always be correlated with the clinical picture, for the correct diagnosis.

In this example, if the biopsy diagnosis is chondrosarcoma, fibrosarcoma, or aneurysmal bone cyst, the physician managing the case should review with the pathology/multidisciplinary team.

The biopsy may not show newly formed bone tissue and, therefore, will not diagnose chondroblastic osteosarcoma or fibroblastic osteosarcoma, nor teleangiectatic osteosarcoma.

When the pathologist does not have data on the patient’s history, physical examination and images, he is restricted to the material he received, which is a sample of the tumor. If you have access to this data, you will be able to make the correct diagnosis, without the need to repeat the biopsy.

Repeating the biopsy delays treatment, increases local aggression and will not guarantee obtaining a sample with newly formed bone tissue.

The pathologist will not be wrong if he makes the report only with the diagnosis of what is on the slide, when he is not aware of the patient’s data and exams.

But the doctor, who manages the case, will make a big mistake if he does not clarify the case, as he is the one who has all the patient’s data, clinical picture, history, physical examination, laboratory and imaging tests.

Author: Prof. Dr. Pedro Péricles Ribeiro Baptista

Orthopedic Oncosurgery at the Dr. Arnaldo Vieira de Carvalho Cancer Institute

Office : Rua General Jardim, 846 – Cj 41 – Cep: 01223-010 Higienópolis São Paulo – SP

Phone: +55 11 3231-4638 Cell:+55 11 99863-5577 Email: drpprb@gmail.com