Eosinophilic granuloma – Pseudo-tumorous lesion

Farber and Green, in 1942, demonstrated that the lesion could occur in a localized or multiple manner in the skeleton and possibly be related to Hand-Schuller-Christian disease and Letter-Siwe disease3.

In 1944, Jaffe and Lichtenstein introduced the term eosinophilic granuloma of bone4. The relationship of this lesion with the systemic forms of the disease was confirmed by Lichtenstein in his 1953 publication, encompassing them under the name Histiocytosis X5.

Currently, this entity is called Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis, which has four distinct clinical forms: Eosinophilic Granuloma, a form restricted to the skeleton, which can be localized or multiple; Hand-Schuller-Christian, chronic and disseminated form; Letter-Siwe, acute or subacute disseminated form and Hashimoto-Pritzker, postnatal form with spontaneous resolution6.

Introduction: Solitary eosinophilic granuloma of the bone is the most common of the four forms of presentation of Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis, representing between 60% and 80% of cases7.

Among benign bone lesions, it is a rare entity, accounting for less than 1%8. It preferentially affects children and adolescents with a male predominance 2:19. Around 80% of patients are under 21 years of age and the majority of these are between five and 15 years of age6,7,9.

Some patients may begin with an isolated bone lesion and later develop multiple bone lesions. These cases can eventually evolve into systemic forms of the disease. When this occurs, it generally happens within the first six months of diagnosis and practically never after a year of evolution, which is a criterion for good prognosis, when no new lesions appear after this period of clinical follow-up10.

Hand-Schuller-Christian Syndrome is the chronic form of Langerhans cell histiocytosis, characterized by systemic involvement with multiple bone lesions, mainly in the skull, exophthalmos and diabetes insipidus, affecting children over 3 years of age10.

Letter-Siwe Syndrome affects children under three years of age, it is the acute or subacute form, also with systemic involvement. It presents with fever, otitis media, recurrent bacterial infections, anemia, hemorrhages, viceromegaly, diffuse and painful adenopathy with skin involvement similar to seborrheic eczema and generalized ostelitic lesions, with frequent progression to death10.

Hashimoto-Pritzker Syndrome is a form of Langerhans cell histiocytosis that affects the skin exclusively. It affects children in the first month of life, manifesting with eczematous eruptions that resolve spontaneously6.

Etiology: Unknown.

Genetics: No significant reports regarding this.

Definition: Eosinophilic Granuloma is a pseudotumor lesion, of unknown etiology, characterized by bone rarefaction that can be solitary or multiple. Microscopically, it presents a profile of mononuclear histiocytic cells, presenting antigens of dendritic origin, known as Langerhans cells, amidst the variable quantity of leukocytes, eosinophils, lymphocytes and giant cells.

Epidemiology: Eosinophilic Granuloma mainly affects the axial skeleton, in this order: skull, pelvis, vertebrae, ribs, mandible, clavicle and scapula.

In the appendicular skeleton the femur, proximal region and diaphysis, humerus and tibia9. Most of the time it affects the diaphysis or metadiaphyseal region, being rare in the epiphysis7.

The spine represents 10% of cases in the pediatric population, the majority in the lumbar region.

In adults, it occurs more frequently in the ribs and less frequently in the spine, respectively 25% and 3%6.

Clinical picture: The most frequent symptom of Eosinophilic Granuloma is localized, throbbing, short-lasting pain, worsening at night associated with local heat and edema. When it affects the skull, this pain can be confused with other causes of headache.

Compromise of vertebral bodies can produce painful scoliosis. Any angular deviations are small, less than 100, as the vertebral flattening is usually uniform and rarely produces neurological symptoms.

In other forms of Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis, systemic symptoms may be present such as fever, skin rush and diabetes insipidus. Hepatosplenomegaly can occur in Letter-Siwe syndrome, which is the most severe form of the disease6

Classification: Eosinophilic granuloma can manifest itself in two clinical forms: Solitary or Multiple .

Laboratory tests: Laboratory changes that can be found are an increase in ESR and CRP, and mild eosinophilia may occasionally occur in the blood count.

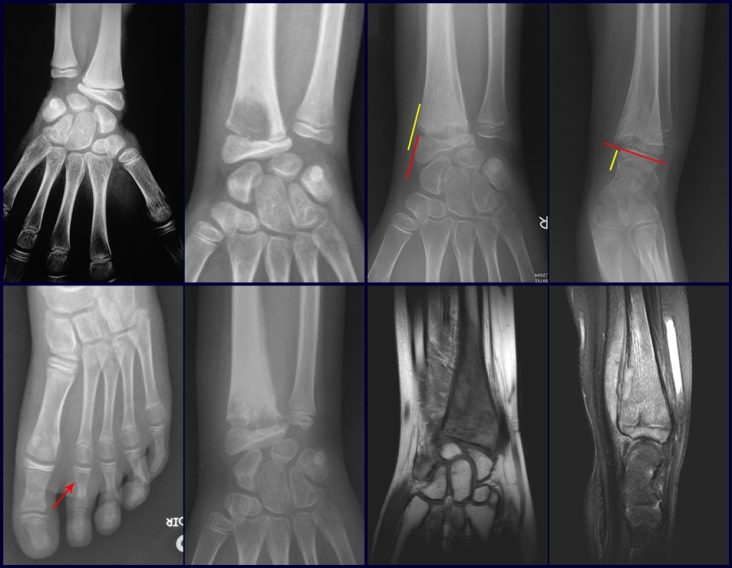

Imaging tests: The radiographic image is of bone rarefaction, rounded or oval, which begins in the medullary bone and progresses with erosion of the cortical bone.

In the initial phase, the edges are irregular and poorly defined.

In the late phase, slight sclerosis may occur around the lesion. In long bones, there is an evident periosteal reaction that appears as multiple thick lamellar layers, which characterizes slow-evolving benign lesions or the reaction of osteomyelitis.

This type of solid periosteal reaction differentiates Eosinophilic Granuloma from Ewing’s Sarcoma, where the periosteal reaction is thin lamellar, due to the rapid evolution of the malignant tumor.

Another radiographic difference between these two lesions is that Ewing’s tumor early presents extra-cortical tumor tissue, with a large volume, which does not occur in Eosinophilic Granuloma.

In flat bones, such as the skull or pelvis, erosion affects both cortices in an irregular and asymmetrical manner, producing the visual impression of a hole within another hole, called a double contour lesion.

In the mandible, destruction of the alveolar bone produces the radiographic impression of floating teeth.

In the spine, the disease affects the vertebral body, with flattening occurring in 15% of cases, producing the so-called flat vertebra of Calvè6. The posterior elements and intervertebral discs are preserved, even when the injury occurs in more than one vertebra.

Pathologic anatomy:

Macroscopic appearance: it has a soft, gelatinous consistency, yellowish in color, necrotic liquefaction is common.

Microscopic appearance: They appear as clusters of large histiocytic cells, with a slightly basophilic cytoplasm, globose, lobulated or indented nucleoli, in these cases similar to a bean seed, which correspond to Langerhans cells.

These clusters are interspersed with giant cells, lymphocytes, numerous eosinophils and areas of necrosis, simulating an abscess. Electron microscopy presents typical cytoplasmic granules called Birbeck bodies11,12.

Immunohistochemistry shows positivity for S-100 protein, vimentin and CD1a11,13.

Diagnosis:

Differential diagnosis: The main radiological differential diagnoses of Eosinophilic Granuloma are Osteomyelitis and Ewing Tumor.

When the lesion occurs in the skull, it must be differentiated from an epidermoid cyst or metastasis. The main histological differential diagnoses are Osteomyelitis and Lymphoma.

Staging:

Treatment: The literature presents reports that expectant treatment or biopsy alone can be indicated as an effective therapeutic strategy for isolated skeletal injuries7,14.

Eosionophilic Granuloma can resolve spontaneously, especially in children. The capacity for the affected bone to rebuild itself exists, as the majority of patients are affected before skeletal maturity, therefore with great potential for remodeling by the growth physes, which are normally not affected15,16.

In our experience, there was resolution in five cases, which regressed only with percutaneous biopsy. The same happens after vertebral collapse in spinal injuries, probably due to the leakage of the contents of the lesion, resembling the drainage of an abscess, with surgical indication in the spine being extremely rare. Cases have been reported where there was complete restitution of the height of the vertebral body15. In our series we had two cases that presented this evolution.

Although there may be spontaneous resolution, the time required is unpredictable, and there may be significant morbidity secondary to intense pain and functional limitation.

Currently, the best therapeutic approach for Eosionophilic Granuloma is to perform a percutaneous biopsy, if possible with immediate diagnosis by frozen section, followed by intralesional corticosteroid infusion (methylpredinisolone – 40mg to 120mg depending on the size of the lesion)7. The anatomopathological result must be subsequently confirmed by histology in paraffin blocks.

Eosionophilic Granuloma can take up to three months to regress, and it may be necessary to repeat the infusion6. In our experience, we had only one case, of an isolated injury to the humerus, which required complementation of the initial treatment in which we performed oral corticosteroid therapy, prednisolone 5mg/24h, for four months. In polyostotic Eosinophilic Granuloma, systemic corticosteroid therapy is used.

When an incisional biopsy is necessary, corticosteroids can be applied locally after curettage of the lesion, which facilitates the resolution of the process. This curettage must be careful, carried out by opening in the form of a narrow slit, longitudinal to the bone, trying not to add greater local fragility. Eventually, the cavity can be filled with a bone graft, but this is generally unnecessary due to the great potential for regeneration that exists.

Radiofrequency was proposed as a percutaneous treatment for Eosionophilic Granuloma, being applied in a second stage, two to four weeks after the biopsy17. The author restricts the technique to small injuries that are at least one centimeter away from the neural or visceral structures, warning of the risk of fractures in the load-bearing limbs. This approach, in addition to increasing costs and causing local morbidity, does not add any advantage to the treatment. The biopsy itself may have been curative, and the infusion of corticosteroids has greater justification, as this is indicated both in isolated cases and in multiple lesions. To date, there are no studies comparing percutaneous techniques with corticosteroid infusion in relation to the use of radiofrequency that justify their use.

Historically, radiotherapy was used in low and fractionated doses for the treatment of Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis. Currently, the indication of radiotherapy for benign lesions is controversial.

In cases of eosinophilic granuloma with more than one skeletal lesion, without visceral involvement, systemic treatment may be indicated for a period of approximately six weeks with corticosteroid therapy (2 mg/kg) and Vinblastine (6 mg/kg).

Prognosis: Solitary lesions of eosinophilic granuloma evolve well in 97% of cases, with biopsy alone or in addition to corticosteroid infusion or surgical treatment 6 .

See also: Eosinophilic granuloma of the radius

Bibliography:

1 SCHAIRER, E. Ueber eine eigenartige Erkrankung des kindlichen Schädels. Zentralbl Allg Patho Pathol. Anat., 71:113, 1938.

2 Otani S, Ehrlich JC; Solitary granuloma of bone simulating primary neoplasm. Am J Pathol 16:479–90. 1940

3 Green WT, Faber S; “eosinophilic or solitary granuloma” of bone. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 24:499-526. 1942

4 Jaffe HL, Lichtenstein L; Eosinophilic granuloma of bone. Arch Pathol 37: 99-118. 1944.

5 Lichtenstein L.: Histiocytosis Pathol. 56:84, 1953

6 Schwartz HS. Orthopedic Knowledge Update: Musculoskeletal Tumors 2. American Academy of orthopedic Surgeons, Rosemont, Illinois. Chapter 12 (128-32), 2007

7 Mavrogenis AF, Abati CN, Bosco G, Ruggieri P. Intralesional Methylprednisolone for Painful Solitary Eosinophilic Granuloma of the Appendicular Skeleton in Children. J PediatrOrthop 2012;32:416–422

8 Chadha M, Agarwal A, Agarwal N, et al. Solitary eosinophilic granuloma of the radius. An unusual differential diagnosis. Acta Orthop Belg. 2007; 73:413–417.

9 Campanacci, M. Bone and Soft Tissue Tumors; Springer-Verlag Wien New York. Second Edition, (54); 857-75. 1999.

10 SCHAJOWICZ, F. Buenos Aires: Osseous Tumors; Talleres de editorial Médica Panamericana SA (9); 464-80. 1981.

11 CHRISTIAN, HA Defects in membranous bones, exosphthalmos and diabetes insipidus: in a usual syndrome of dyspituitarism: a clinical study. Med.Clin. North. Am., 3:849, 1920.

12 ARCECI, RJ; BRENNER, M.K.; PRITCHARD, J. Controversies and new approaches to the treatment of Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Hemtol. Oncol. Clinic. North. Am., 12:339, 1998

13 ALBRIGHT, F.; REIFNSTEIN, EC The parathyroid glands and metabolic disease. Baltmore, Williams & Wilkins, 1948.

14 Plasschaert F, Craig C, Bell R, et al. Eosinophilic granuloma. A different behavior in children than in adults. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2002;84:870–872.

15 Greenlee JD, Fenoy AJ, Donovan KA, et al. Eosinophilic granuloma in the pediatric spine. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2007; 43:285–292.

16 Sessa S, Sommelet D, Lascombes P, et al. Treatment of Langerhans cell histiocytosis in children. Experience at the Children’s Hospital of Nancy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1994; 76:1513–1525.

17 Corby RR, Stacy GS, Peabody TD, et al. Radiofrequency ablation of solitary eosinophilic granuloma of bone. Am J Roentgenol.2008;190:1492–1494.

Author: Prof. Dr. Pedro Péricles Ribeiro Baptista

Orthopedic Oncosurgery at the Dr. Arnaldo Vieira de Carvalho Cancer Institute

Office : Rua General Jardim, 846 – Cj 41 – Cep: 01223-010 Higienópolis São Paulo – SP

Phone: +55 11 3231-4638 Cell:+55 11 99863-5577 Email: drpprb@gmail.com