For better understanding, we suggest that you first read the chapters:

https://oncocirurgia.com.br/introducao-ao-estudo-dos-tumores-osseos/

Biopsy Considerations

Biopsy – Concept – Types – Indications – Planning

1. Only after the clinical evaluation, with careful history taking and clinical examination, which will allow us to raise diagnostic hypotheses, should we request additional tests.

With the analysis of complementary exams, we should verify:

A- If our hypotheses are compatible with the tests and continue to qualify as possible diagnoses;

B- A new hypothesis has appeared, which we had not thought of, and we will have to redo our clinical reasoning.

C- If the exams are correct, well done, images centered on the lesion, with good quality or we will have to repeat them.

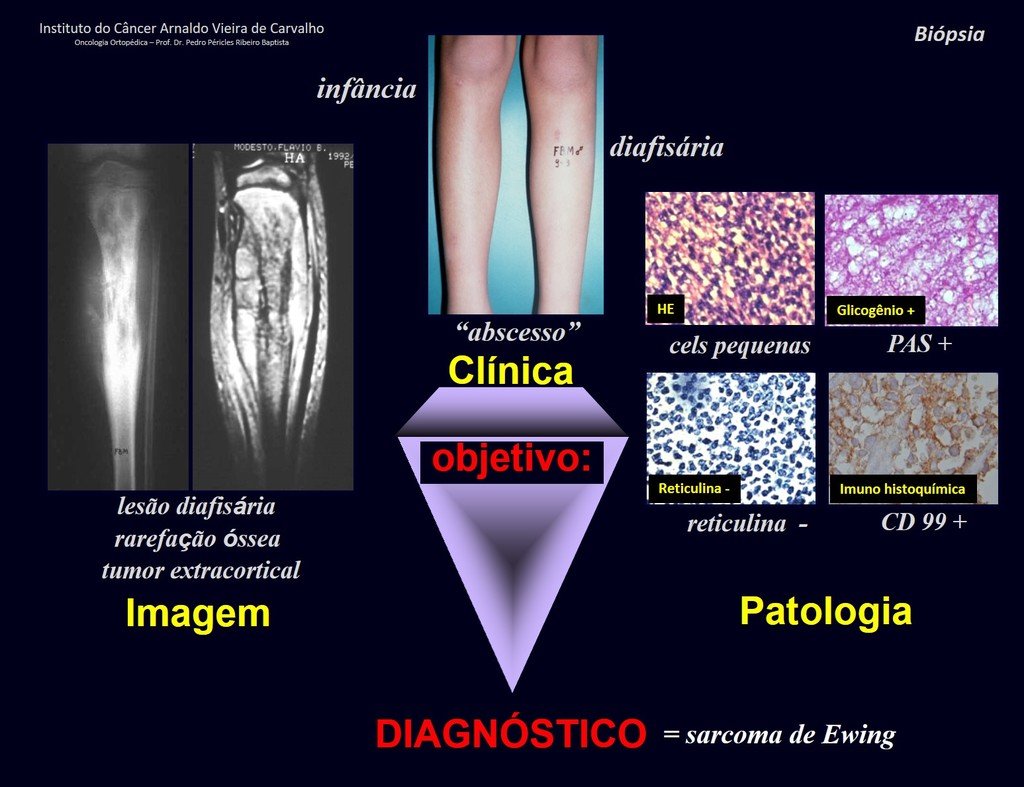

2. Diagnosis hypotheses must first be made through clinical examination, laboratory tests and imaging.

3. Pathology must be used as a “tool” to confirm or not confirm the suspected diagnosis.

If the anatomopathological examination reveals a diagnosis that was not on our list, we must reanalyze the case, redo our reasoning. If there is no clinical, radiological and anatomopathological correlation , something may be wrong and we will need to review it together, in a multidisciplinary team, to determine the best course of action. New biopsy?

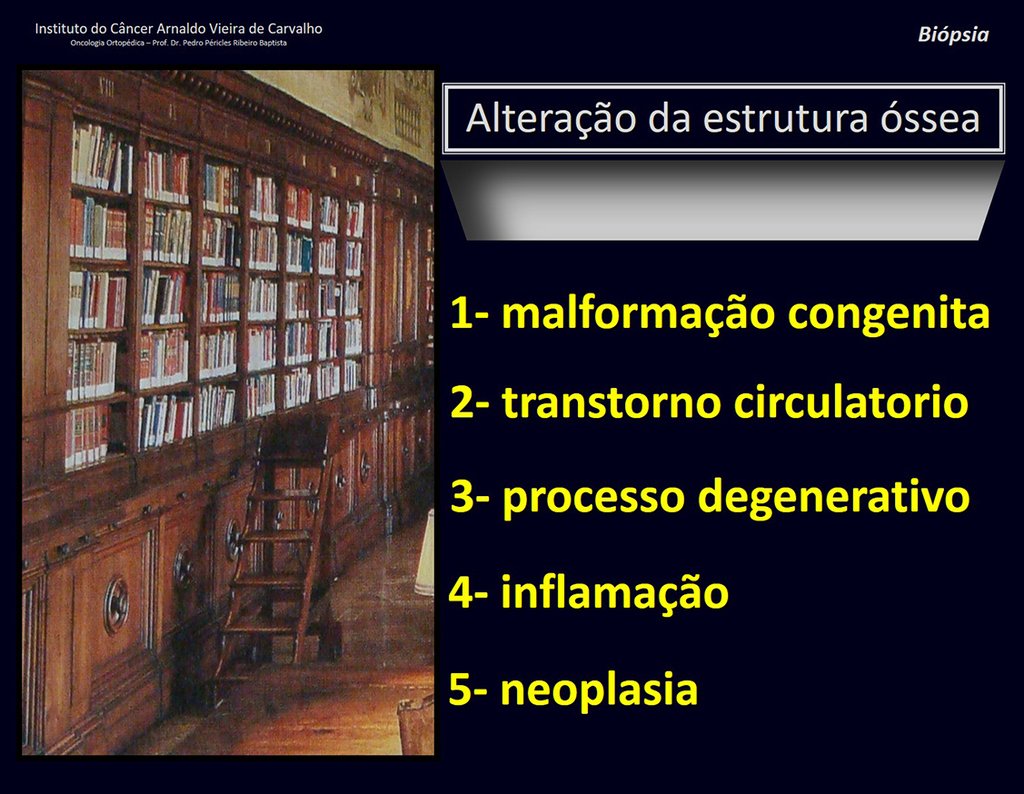

4. To reason about the diagnosis, it is first necessary to frame the condition we are analyzing within the five chapters of pathology, figures 1 and 2.

Biopsy – concept – types – indications – planning

5. If we conclude that our patient has a neoplasm, we need to carry out the reasoning exercise already described in the Introduction to the Study of Tumors and Tumor Diagnosis chapters (Links: https://oncocirurgia.com.br/introducao-ao-estudo- dos-tumores-osseos/ and https://oncocirurgia.com.br/diagnostico-dos-tumores/ ).

After these steps, we can think of the biopsy as a “tool” for the definitive diagnosis.

Before we address the topic “biopsy”, let’s analyze some cases.

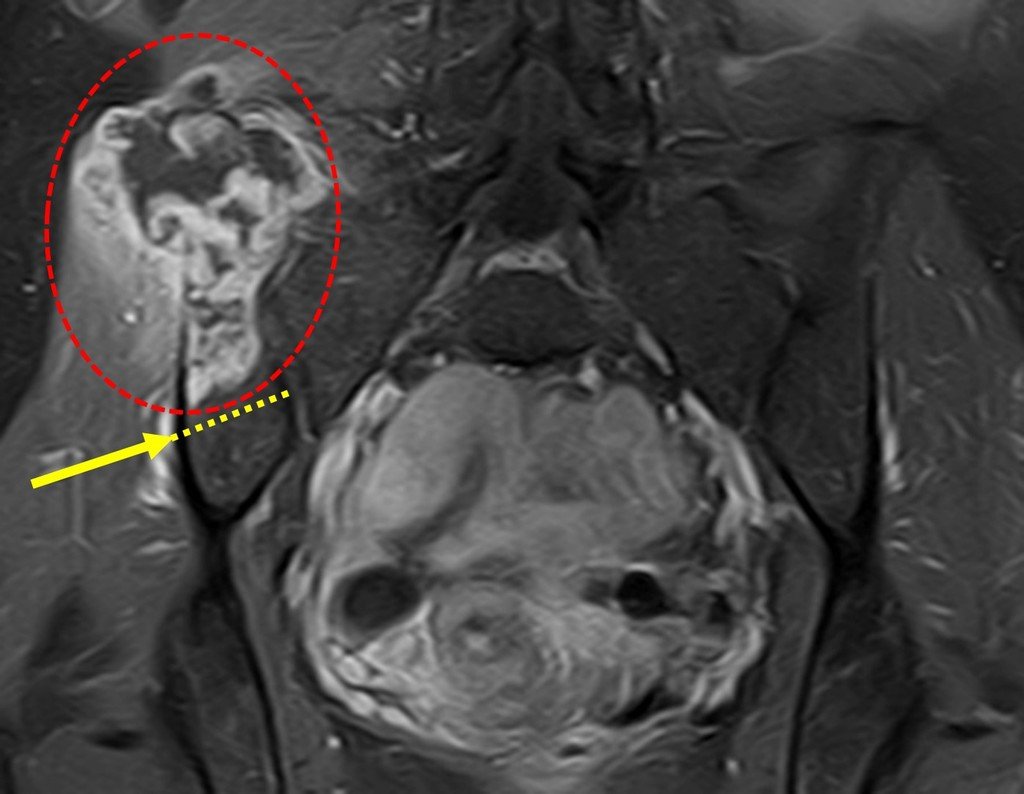

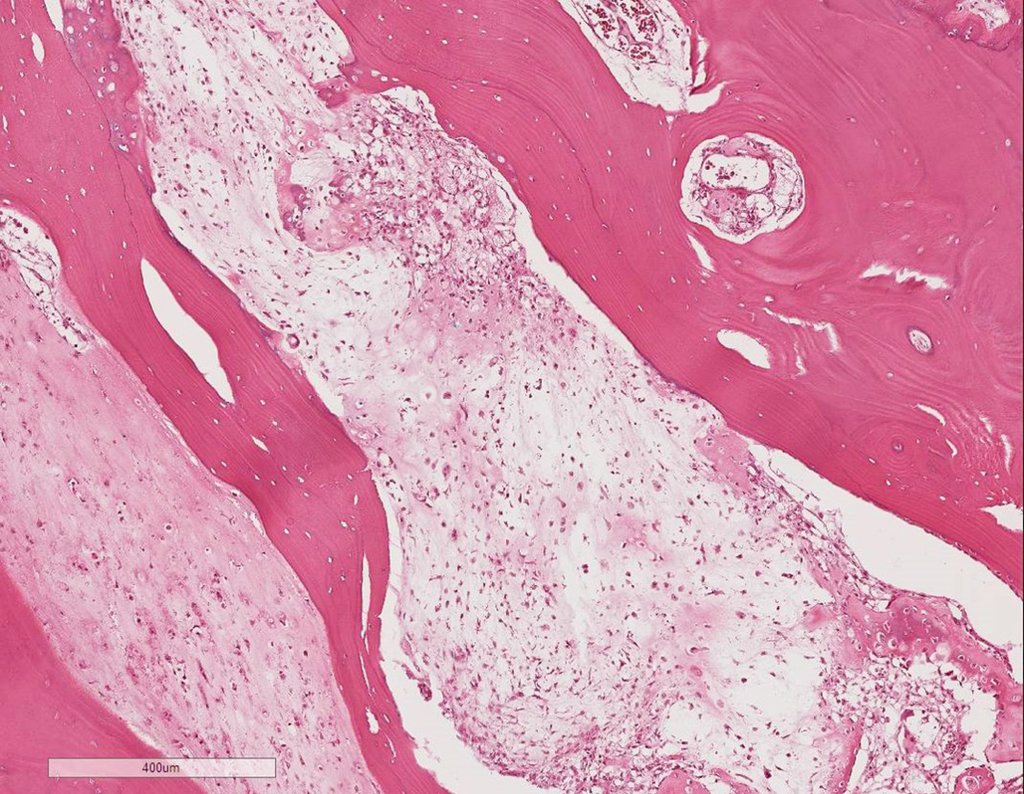

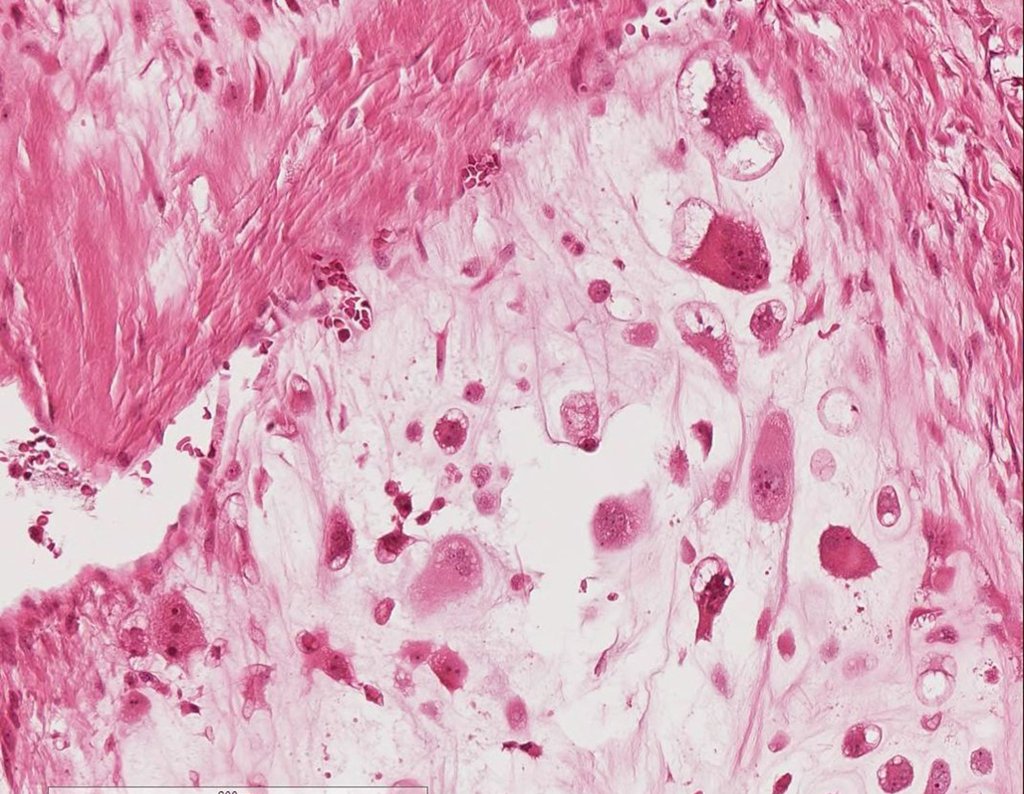

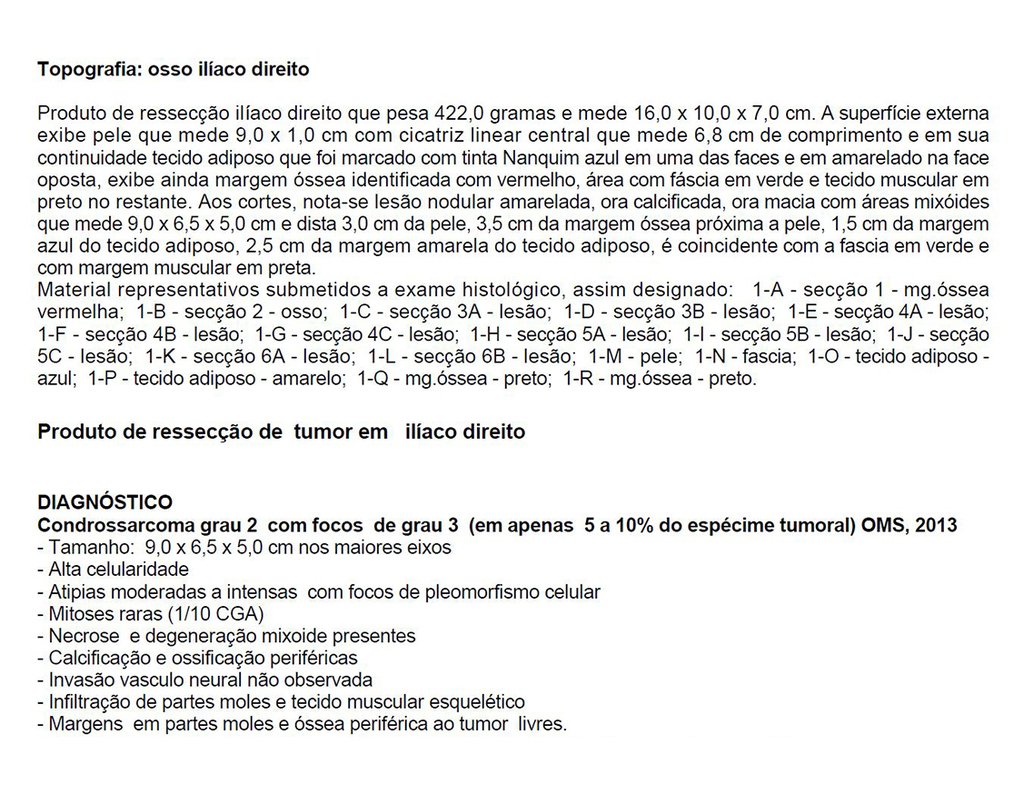

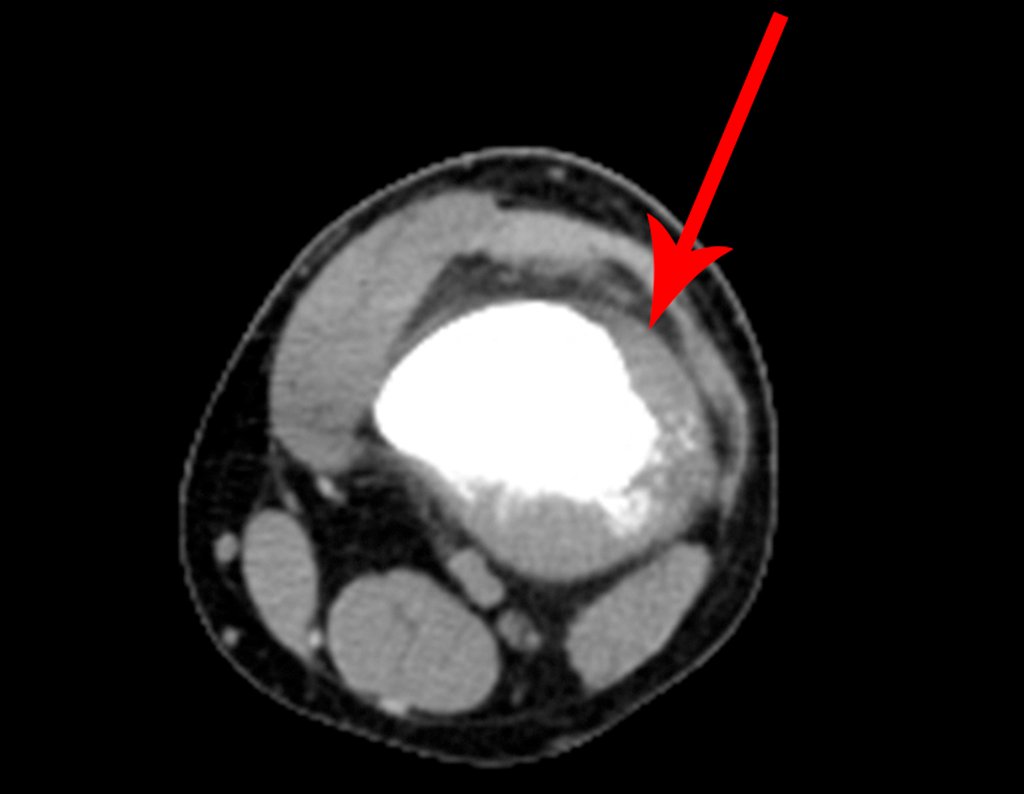

Patient A : figures 3 and 4.

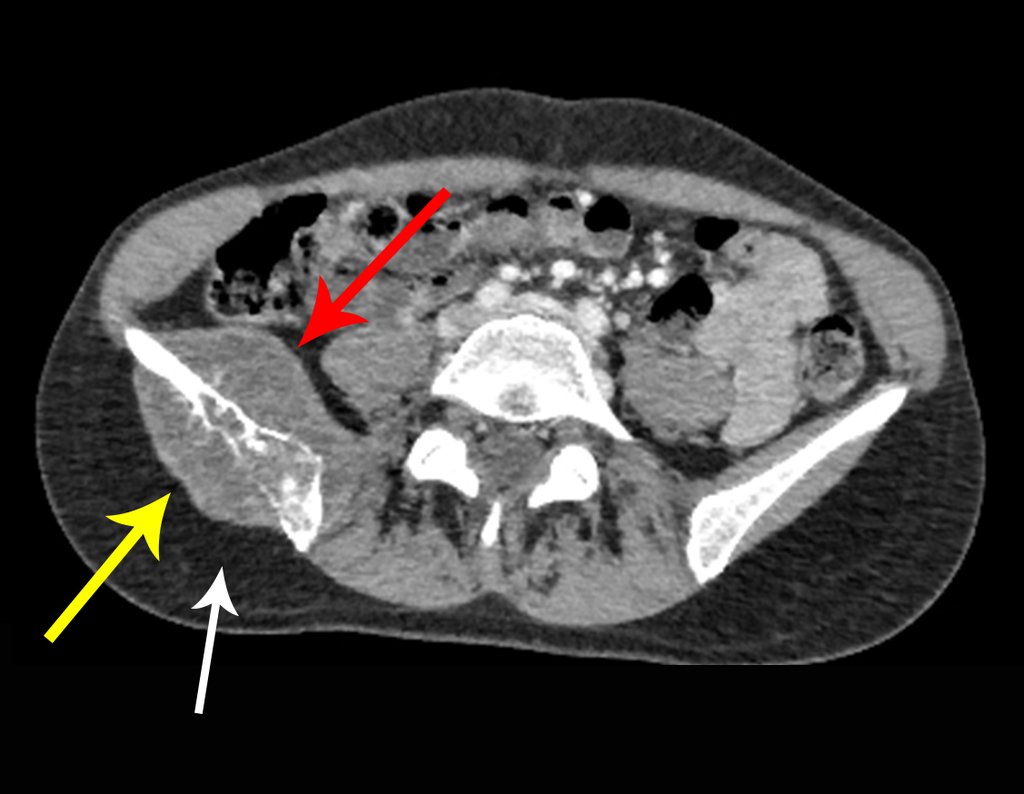

Thirty days ago, they requested a biopsy of an abdominal wall lesion on a patient admitted for investigation.

The patient’s doctor found me in the radiology room, analyzing the CT scan.

Following the “how I think” about injuries I asked myself: – what structures form the abdominal wall? The. skin (squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, melanoma) ; B. subcutaneous (lipoma, liposarcoma) ; w. muscular fascia (desmoid fibroma) ; d. striated muscle (fibroma, fibrosarcoma, desmoid fibroma, rhabdomyosarcoma) ; It is. vessel (hemangioma, leiomyosarcoma) ; f. peritoneum and abdominal cavity (no longer my jurisdiction).

It seemed like an extensive lesion and I suggested that I look for a surgeon in the area, as I wouldn’t know how to drive if it was a malignant neoplasm. Ideally, the biopsy should be performed by the person who will operate on the patient.

He told me that the patient was jaundiced, an ultrasound and several laboratory tests had been performed, insisting that I perform a biopsy. I asked him some information and as I didn’t know how to find out, I suggested that we visit the bed. We could extract the clinical history and examine the patient.

The patient reported being asthmatic and reported that the symptom began abruptly after a coughing fit eleven days ago, in a sudden change of weather, cold and drizzling. He had severe pain in the anterior wall of the abdomen, where a “ball” appeared. The bulging and pain were decreasing and the side wall had hardened.

Leaving the room, I suggested that we not do a biopsy, that we discharge the patient, that the jaundice with elevated bilirubin was the result of a large hematoma that had infiltrated the lateral wall, due to the spontaneous rupture of the anterior rectus abdominis. This lesion was already undergoing repair and the biopsy would only show the scarring inflammatory process (with the risk of proliferative myositis).

Still not convinced, he asked me if I had ever seen a case of spontaneous rupture of the rectus abdominis muscle. I answered no, but that was what common sense said. Going down the stairs we met a general surgeon and I asked him about the matter. This clarified that it was common in patients with chronic bronchitis who were taking corticosteroids, as was the case with our patient. The clinical history made the diagnosis.

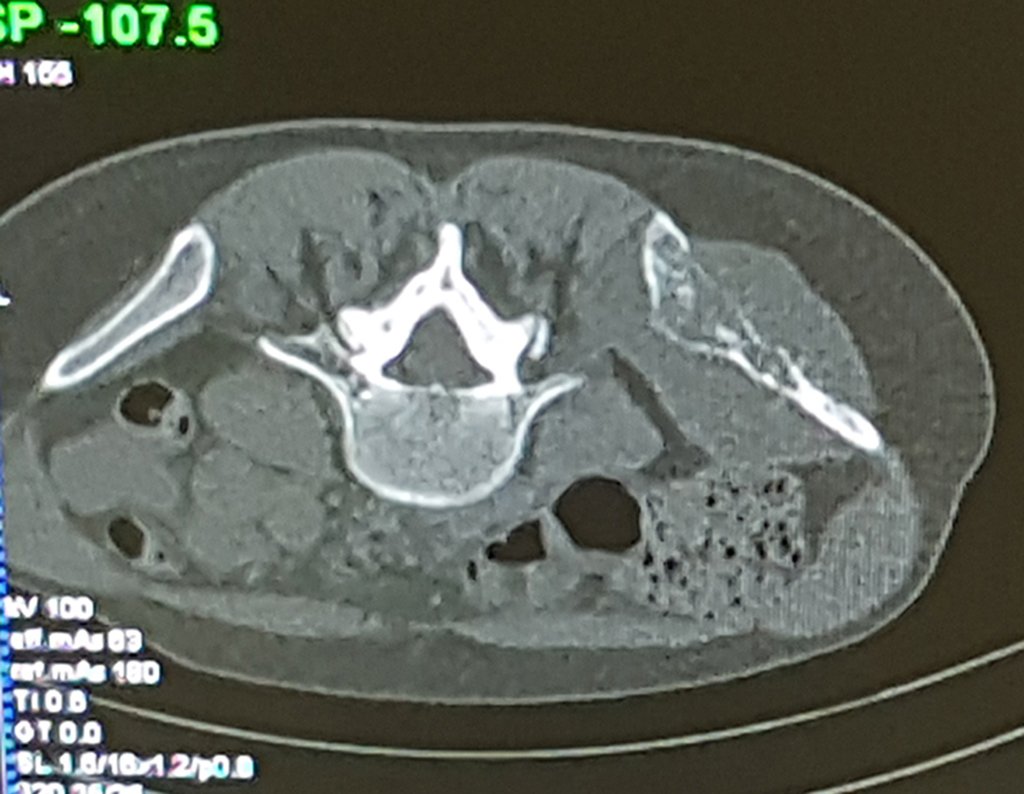

Patients B : Figure 5.

At the outpatient clinic, the resident asks:

– “By which access route should we perform the biopsy?”

I see the image and ask: – How old is the patient?

– “Um… Dona Maria, how old are you?”

I reflect in silence, evaluating the learner’s lack of knowledge. The patient responds 67 years old DOCTOR!

… Sixty-seven years, multiple lesions, metastasis? Multiple myeloma? Brown tumor of hyperparathyroidism? – How long has she had symptoms?

– “Um… Dona Maria, how long have you had this problem?”

In the medical record I see symptoms of pain in the ischial tuberosity noted , measurements of Ca ++ , P ++ , FA, Na + , K + , protein electrophoresis, blood count, ESR, blood glucose, urea, creatinine, ultrasound, x-rays,…, …

When examining the patient, I observed that the “tumor” is anterior , in the inguinal region, and not posterior , as noted in the medical record, “ischial tuberosity”. The patient had not been examined !!! She had an inguinal-crural hernia. Pelvic x-ray images represent gas from the intestine. The “biopsy” would result in intestinal perforation. The physical examination made the diagnosis.

Patient C : Figure 6.

Passing through the emergency room, the person on duty asks:

– “Doctor, what tumor do you think this patient has? Can we schedule the biopsy?”

The resident knew nothing about the history and had only taken the frontal x-ray!!! When asked, the patient reports that the inflammatory symptoms began six months ago, with hot pain and the release of purulent secretions. When it was open, secreting, the symptoms improved. When he closed the fistula it started to swell, hurt and he had a fever.

With difficulty, as the patient often withholds information, we learned that he had been injured in the thigh two years ago, when he jumped over the guardrail of a house, which bled a lot, but did not seek treatment ( clinical history ) . We requested a lateral x-ray which confirmed that it was a foreign body. The spear tip of the grid was surrounded by solid periosteal reaction, giving the false impression of a sclerotic tumor. Appropriate imaging confirmed the diagnosis.

After these important considerations, we will study the controversial topic of biopsy.

WE NEED:

1- Define the hypotheses of possible diagnoses, for our case, firstly with the clinical history and physical examination ;

2- Carry out laboratory and imaging tests, to corroborate or not our hypotheses, our reasoning and

3- Only after these steps can we perform the biopsy, for the pathology to “ recognize the signature ” of the diagnosis, previously thought out with our anamnesis, physical, laboratory and imaging examination.

“Pathological anatomy is not a short path to diagnosis. We must always correlate it with the clinic, laboratory and imaging tests”.

Regarding biopsy, we can subdivide musculoskeletal lesions into three groups:

- Cases in which CLINICAL – RADIOLOGICAL diagnosis (image) is sufficient for diagnosis and treatment, and biopsy is not indicated.

- Cases that may not require this procedure due to difficulty in histological diagnosis, and due to the characteristics of clinical and radiological aggressiveness , the necessary surgical procedure should not be altered.

- Cases that require pathological confirmation for chemotherapy treatment prior to surgery

We will discuss the three groups, analyzing some examples, figures below.

GROUPS 1 and 2 : Biopsy is not necessary or does not change management.

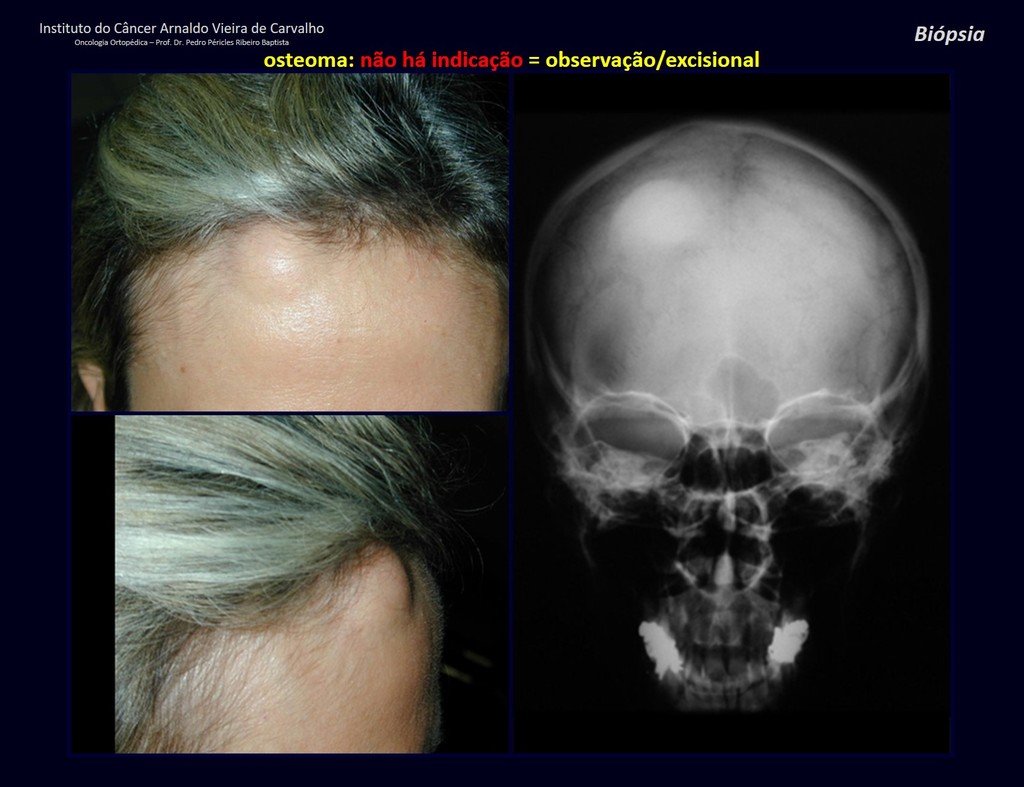

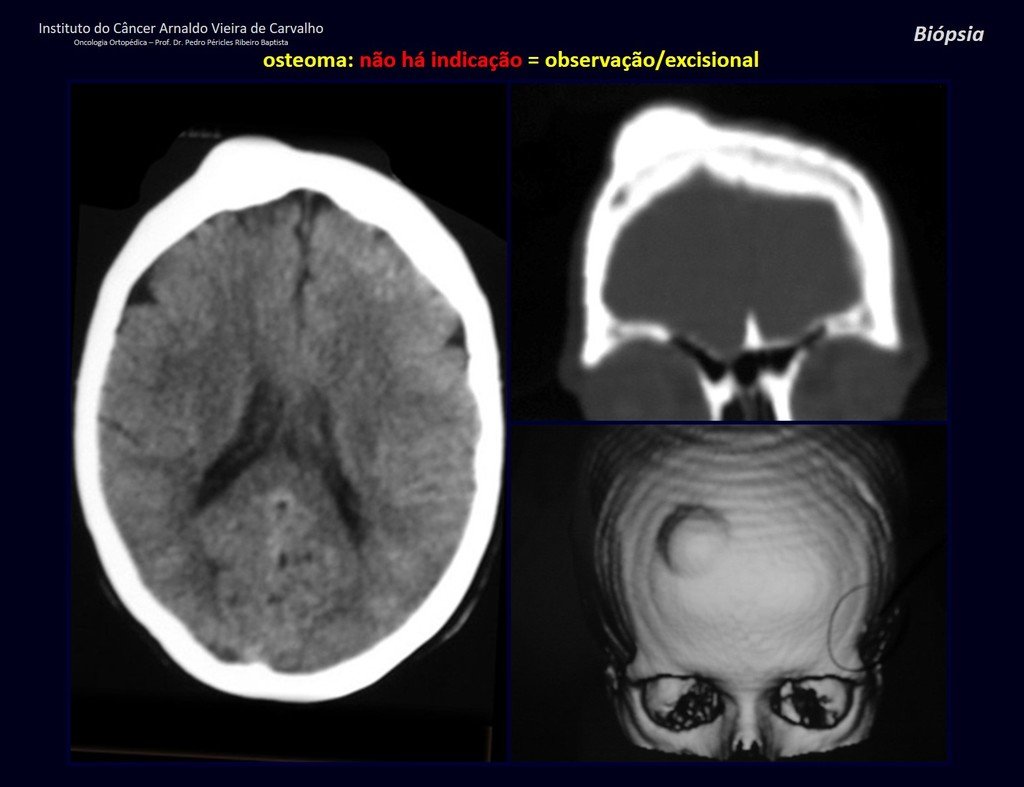

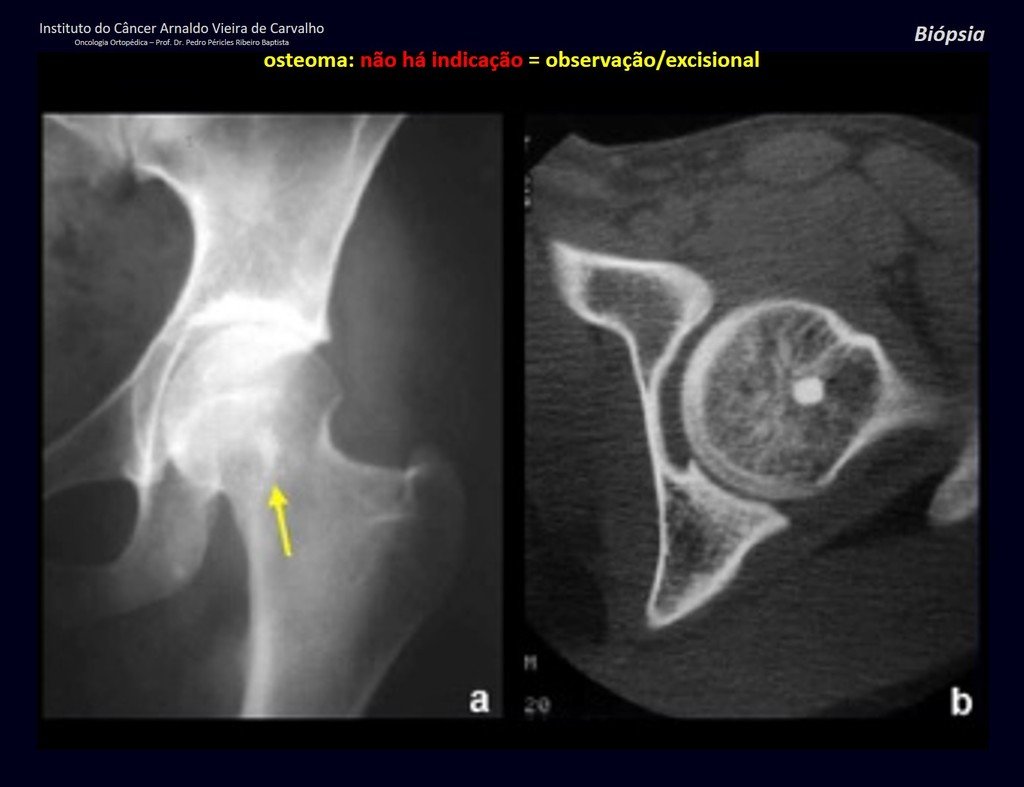

1a . OSTEOMA, figures 13 to 18.

IDENTITY: Benign, well-defined neoplastic lesion, characterized by a homogeneous, sclerotic and dense tumor, mature bone tissue. It’s bone within a bone.

These lesions are well-defined, homogeneous, without symptoms. They are diagnosed by occasional imaging findings or by presenting aesthetic changes. Occasionally, they may be symptomatic, as in a case where the nasal cavity was obstructed, making breathing difficult. The diagnosis is clinical and radiological, and does not require a biopsy. Treatment is restricted to observation and monitoring. They are rare and occasionally operated on.

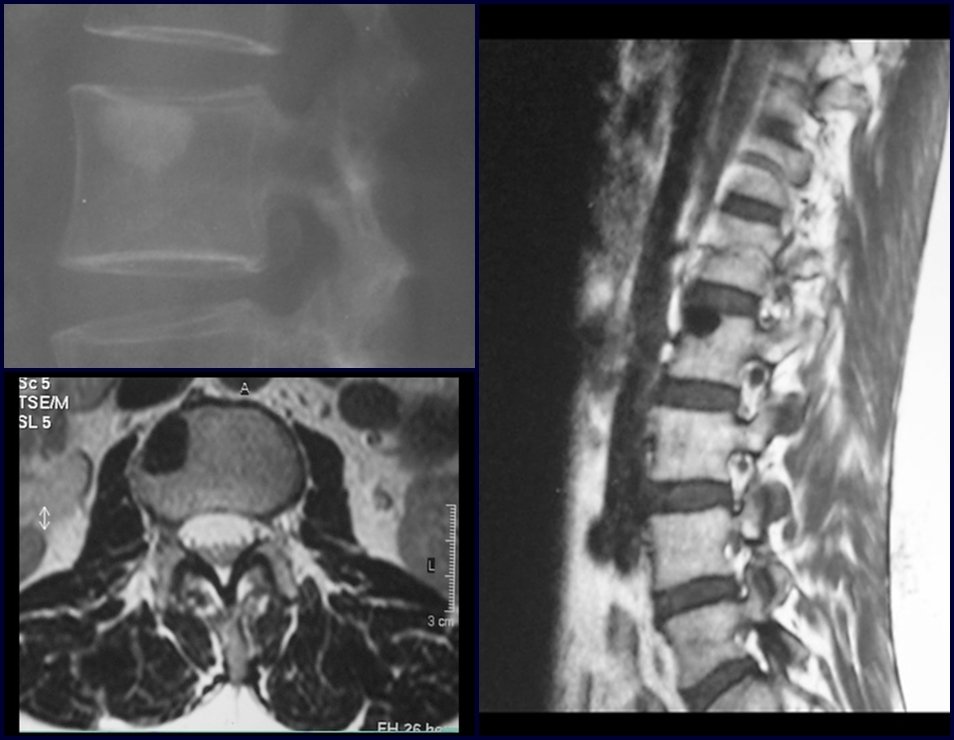

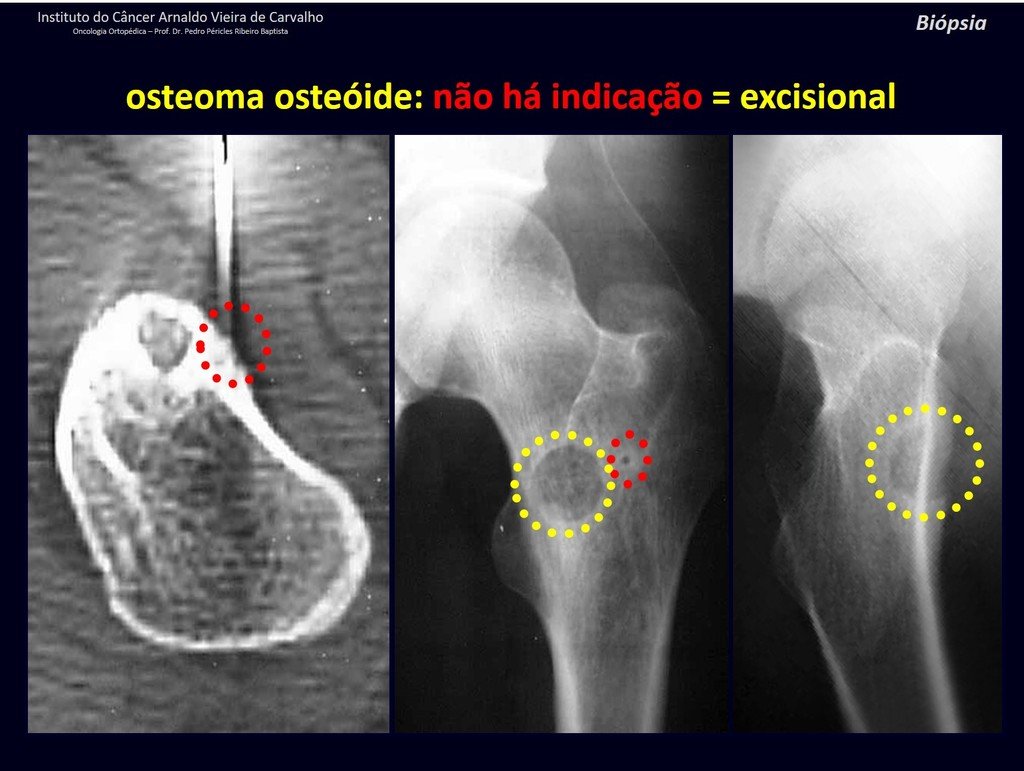

1b . OSTEOID OSTEOMA, figures 19 to 26.

IDENTITY: Benign neoplastic lesion, characterized by a circumscribed tumor, up to approximately one centimeter in diameter, which presents a central osteoid niche, surrounded by a halo of sclerosis and located in the cortex of the long bones, the most compact part.

The femoral neck region is covered by a thin periosteum that does not present a periosteal reaction. This makes it difficult to locate the lesion during surgery.

Making a hole in the cortical bone, close to the lesion, guided by radioscopy, will facilitate the operation.

After this marking, we perform a tomography to measure the distance from the hole to the center of the lesion, locating it. See the complete technique at: http://osteoid osteoma resection technique

Osteoid osteoma is a lesion of the cortical bone. In the spine, it occurs in the pedicle, which is the most compact, hardest part, resembling the cortex.

It has a central niche with a halo of sclerosis around it and does not exceed one centimeter.

There is no such thing as a “giant osteoid osteoma”, larger than 1.5 cm, as in this situation there is cortical erosion, there is no delimitation by the sclerosis halo and, although it may present similar histology, we are dealing with an osteoblastoma, which is a benign lesion. , but locally aggressive. Osteoblastoma may or may not be associated with an aneurysmal bone cyst and may also require a differential diagnosis with teleangiectatic osteosarcoma. Read also: http://osteoid osteoma

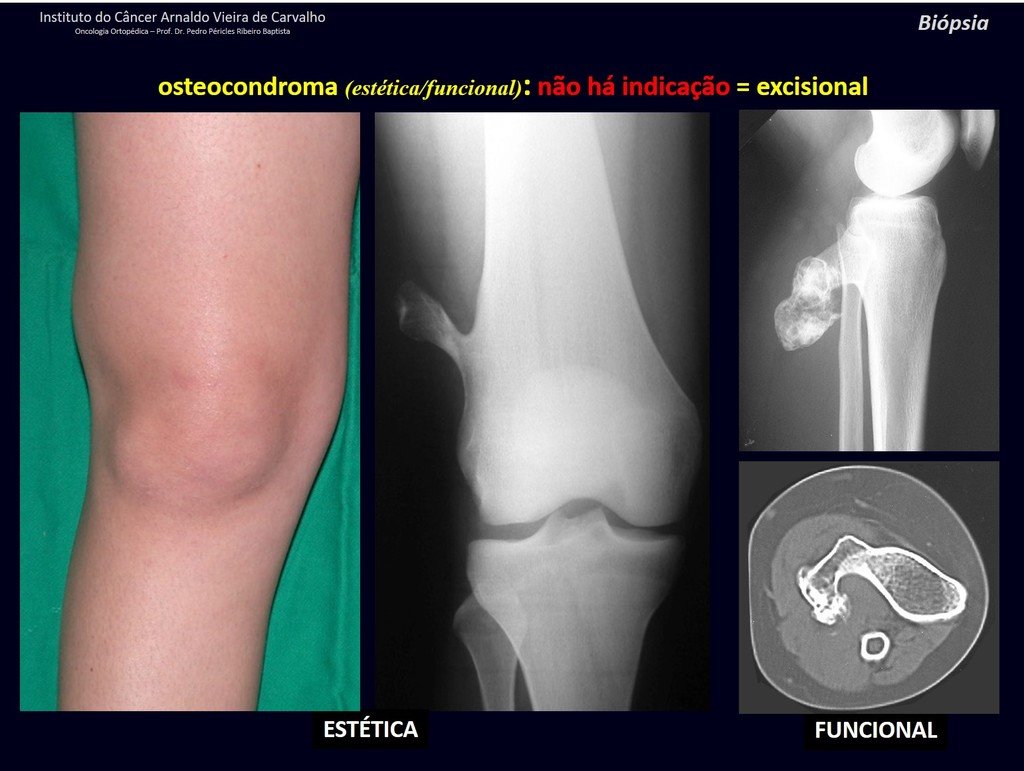

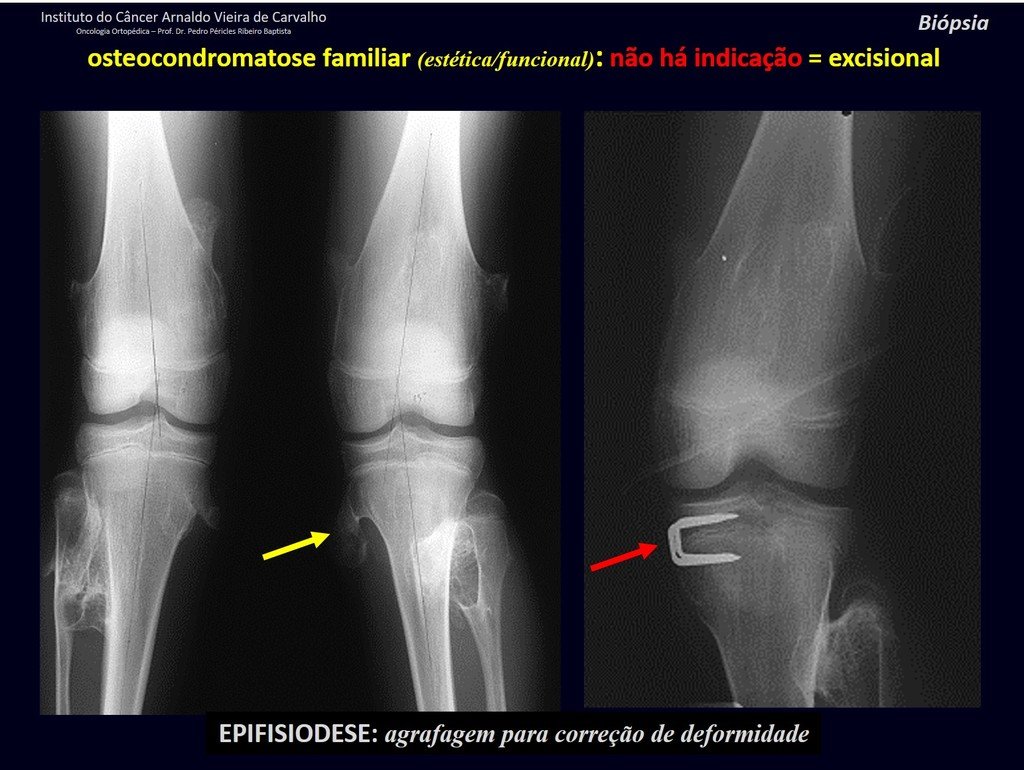

1c . OSTEOCHONDROMA, figures 27 to 32.

IDENTITY: It is an exostosis in which the central cancellous bone continues with the medullary of the affected bone and the dense peripheral, cortical layer of the tumor continues with the cortical layer of the affected bone. It presents with an enlarged, sessile, or narrow, pedicled base . It can be single or multiple (hereditary osteochondromatosis).

Osteochondromas require surgical treatment when they alter aesthetics or function, displacing and compressing vascular-nervous structures, limiting movement or generating angular deformities. It is the most common benign bone lesion.

They generally grow while the patient is in the growth phase. When an osteochondroma increases in size after completion of skeletal maturity, it may mean post-traumatic bursitis or malignancy to chondrosarcoma and should be treated as such, resecting with an oncological margin.

Solitary osteochondroma has a 1% malignancy rate. Multiple osteochondromatosis can reach 10%.

The diagnosis of osteochondroma is clinical and radiological and does not require a biopsy for treatment.

Read: http://osteochondroma

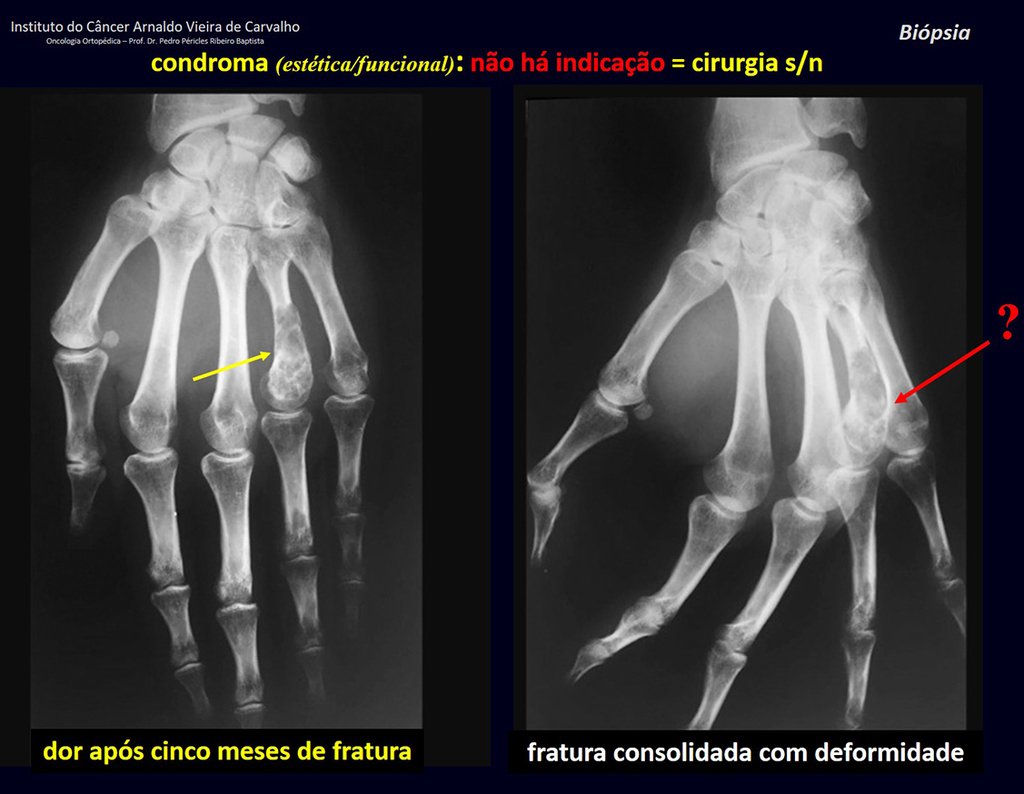

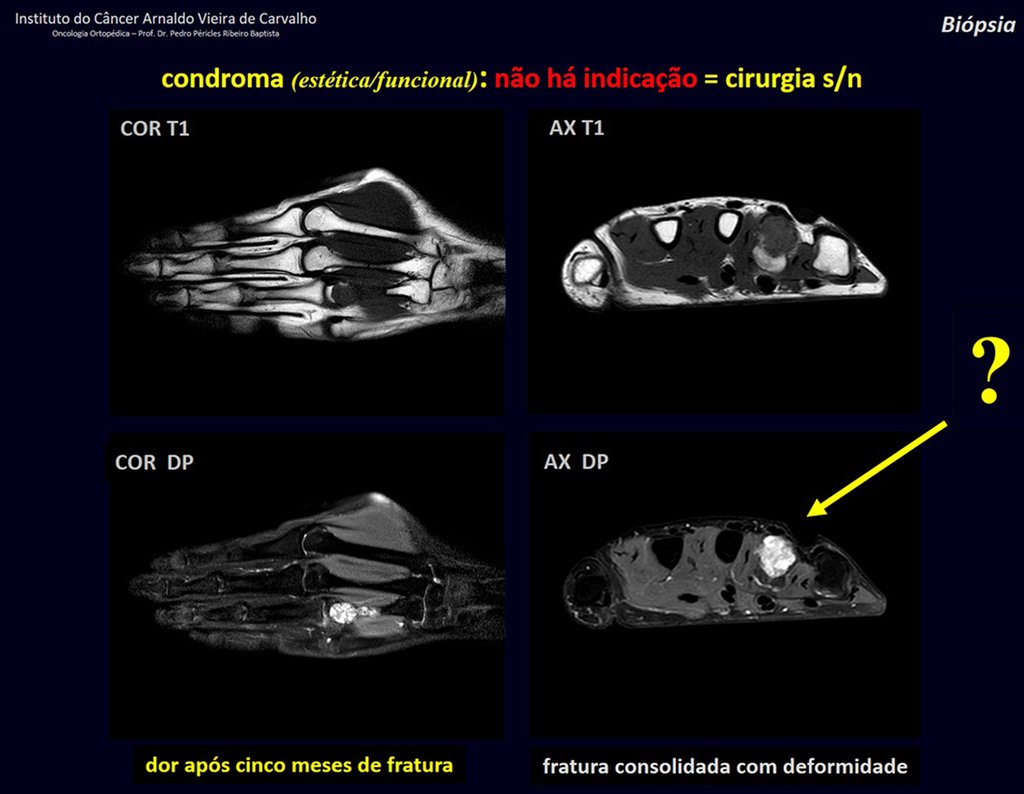

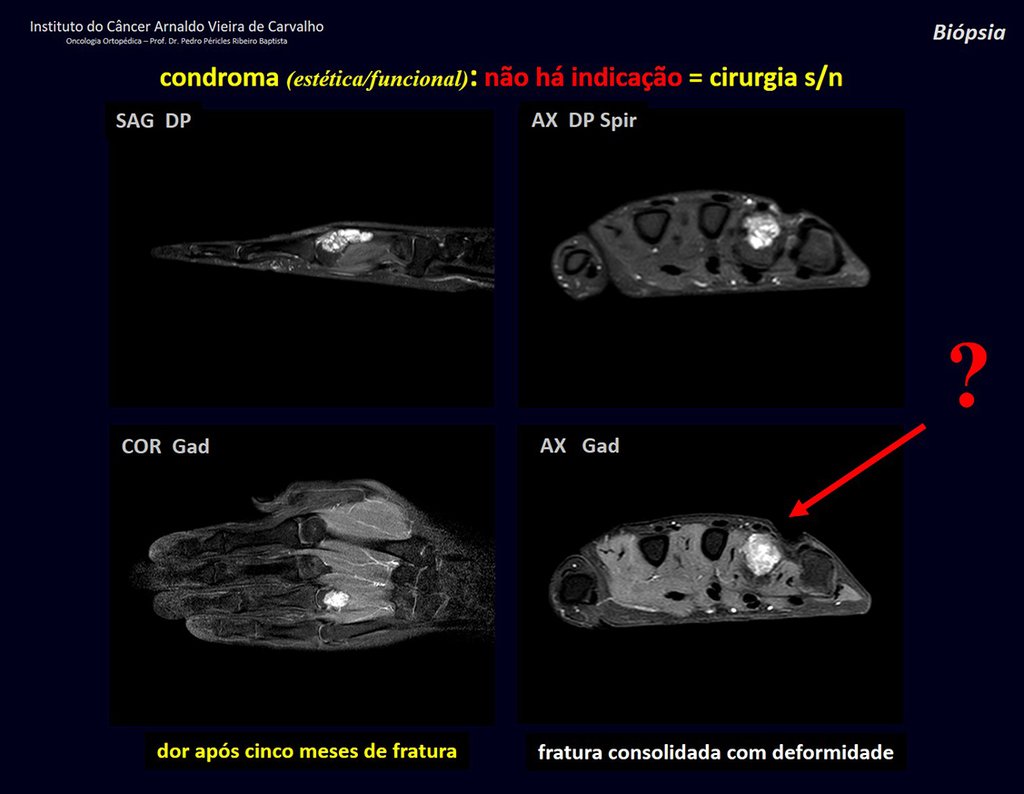

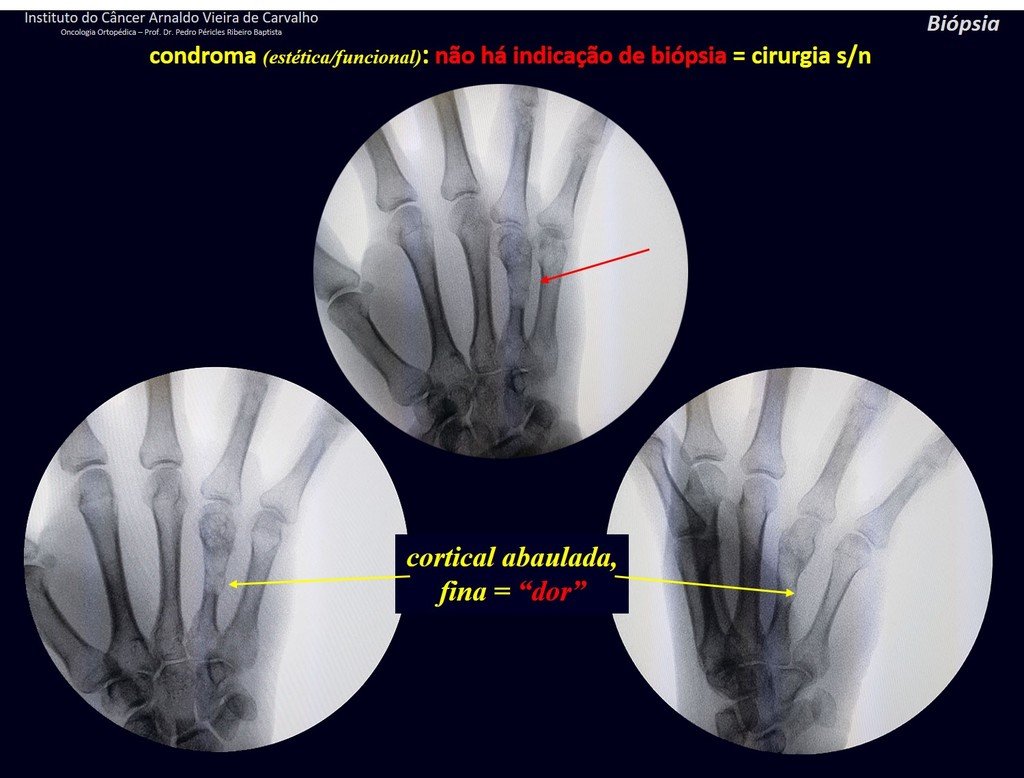

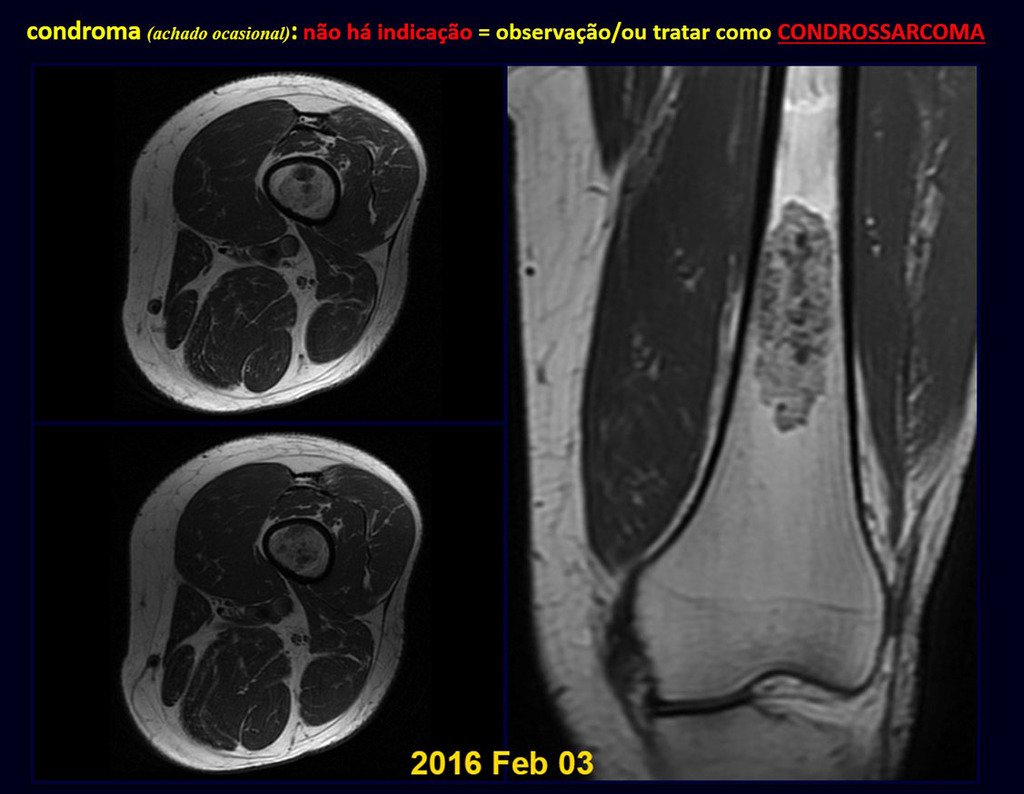

1d . CONDROMA, figures 33 to 50.

IDENTITY: Benign, painless, cartilage-forming tumor with foci of calcification in the short bones of the hands and feet, diagnosed by chance or due to deformity or fracture. It can be solitary or multiple (enchondromatosis, Maffucci syndrome, Ollier disease).

In the fingers and toes, cartilaginous lesions generally behave benignly.

The eventual unwanted evolution to chondrosarcoma, resulting from curettage surgery in these locations, does not compromise the possibility of a cure, as complete resection of the finger, which is the treatment of chondrosarcoma , would continue to be possible.

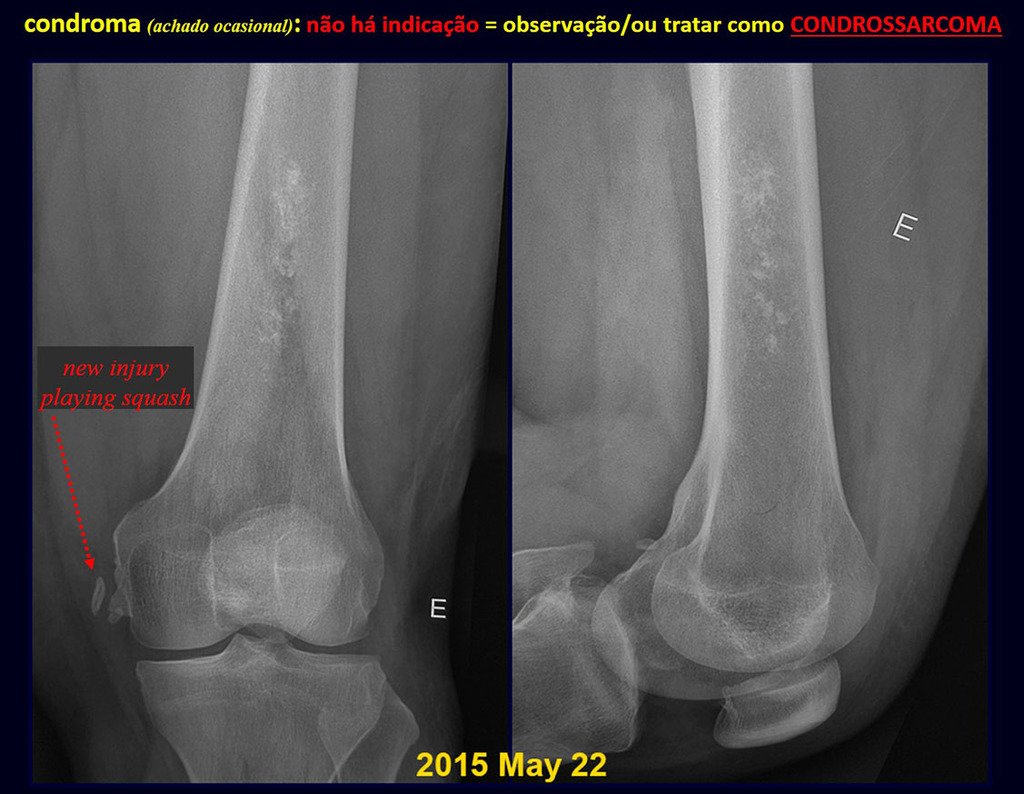

CONTROVERSY : CHONDROMA OR CHONDROSSARCOMA GRADE I?

Chondroma occasionally occurs in the metaphysis of long bones (distal femur, humerus and proximal tibia) and limb roots (shoulder, pelvis) . In these cases, it can be confused with bone infarction or grade I chondrosarcoma.

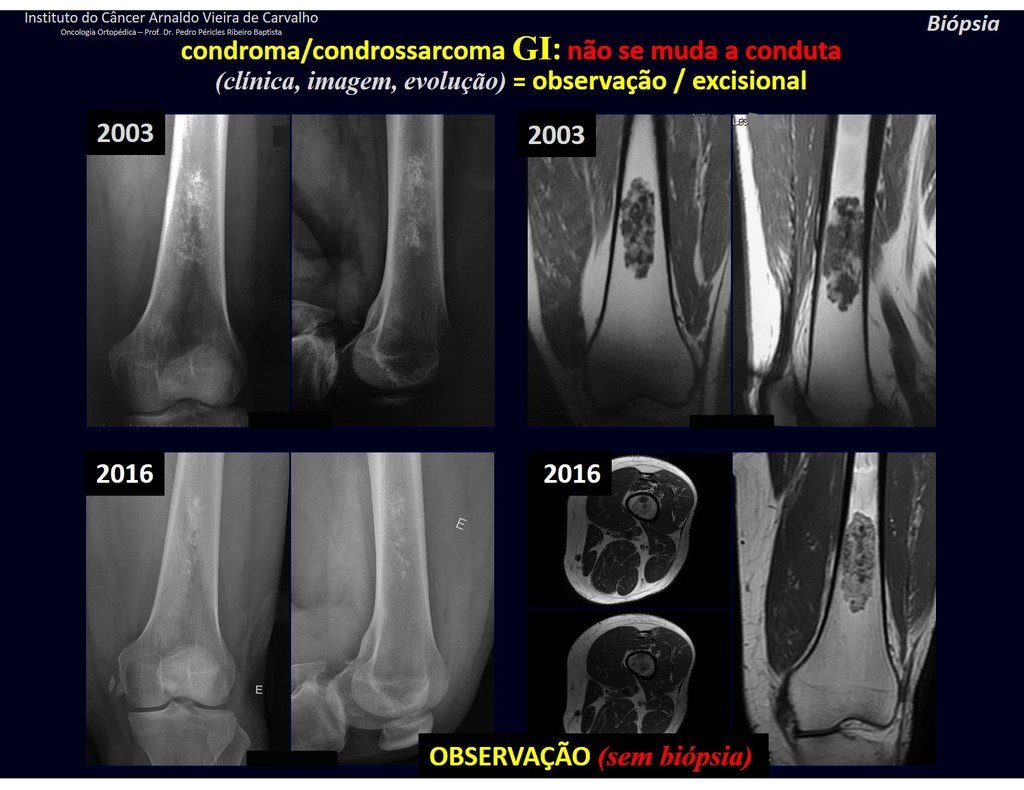

In occasional findings, as the anatomopathological diagnosis between chondroma and grade I chondrosarcoma is controversial , it is preferable not to perform a biopsy and monitor clinically and radiographically whether there is progress.

Grade I chondrosarcoma is slow to evolve, which allows monitoring, enabling observation for a safe diagnosis of its activity or not.

The exams are repeated at one, three and six months, and then annually. The tumor must be treated surgically as chondrosarcoma at any time if comparison between images reveals changes in the lesion.

If the injury remains unchanged, the best course of action is to continue monitoring. Some patients ask until when? The answer is: – Always. Reevaluation should continue regardless, whether the patient undergoes surgery or not.

Treating an asymptomatic lesion, a casual finding, without changing the image with minor surgery is “ overtreatment”, which will also require follow-up or worse, if the anatomopathological examination reveals malignant histology.

Exemplifying this conduct, we will analyze the following case, followed for 14 years, figures 39 to 42.

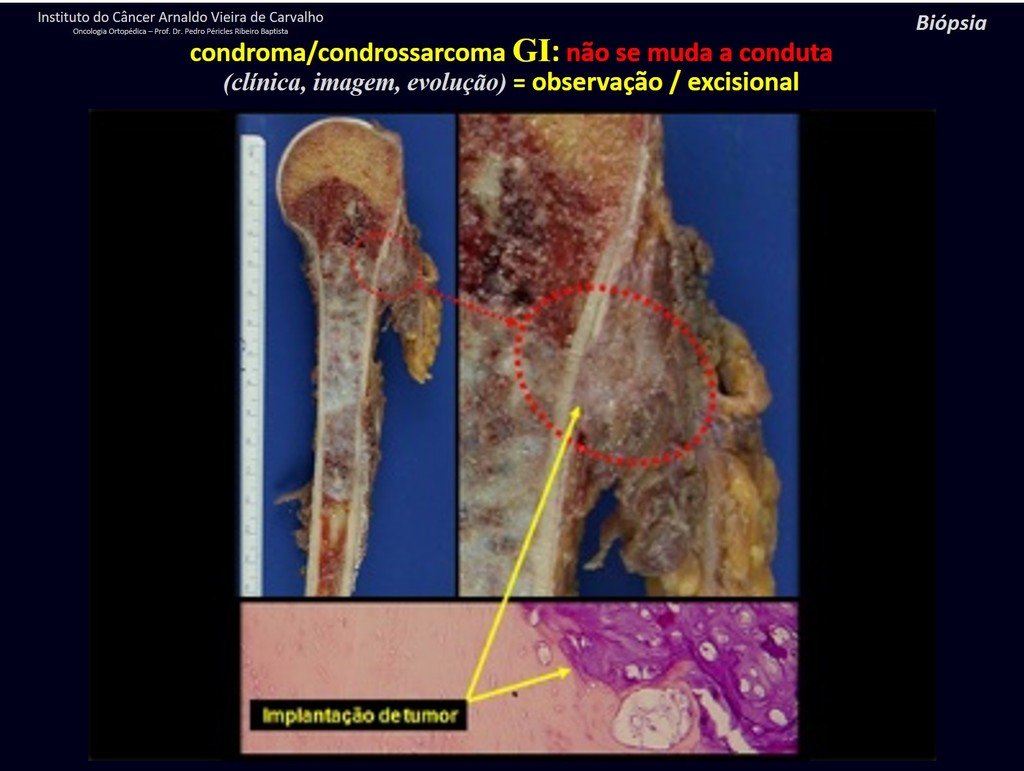

CHONDROMA or CHONDROSSARCOMA? In these cases common sense must prevail, he warns us that the paper accepts any writing.

We must base ourselves on the clinical behavior of the lesion. Was there a change or not? If we choose to perform a biopsy, we can only add whether or not it is a “cartilaginous lesion” . We cannot change our behavior: OBSERVE OR OPERATE AS CHONDROSSARCOMA . To be safe, if we choose to operate, we must treat it surgically as chondrosarcoma, which is our only “ tool” , as they do not respond to chemotherapy or radiotherapy.

¨The doctor can perform the biopsy , as it is an academic procedure, which gives him more support as to whether it is a cartilaginous lesion. But you should not operate with a curettage technique , such as chondroma, as latent chondromas of long bones, casual findings, do not require surgical treatment but rather observation. The biopsy hinders this observation because we will not know whether the pain and changes in the image, which may occur after the biopsy, would be due to the aggression of the biopsy or whether it is a chondrosarcoma manifesting itself. In conclusion, if the doctor chooses to intervene, he must operate on chondrosarcoma . We also remember that surgery, performed using any technique, will not eliminate the need for observation and monitoring¨.

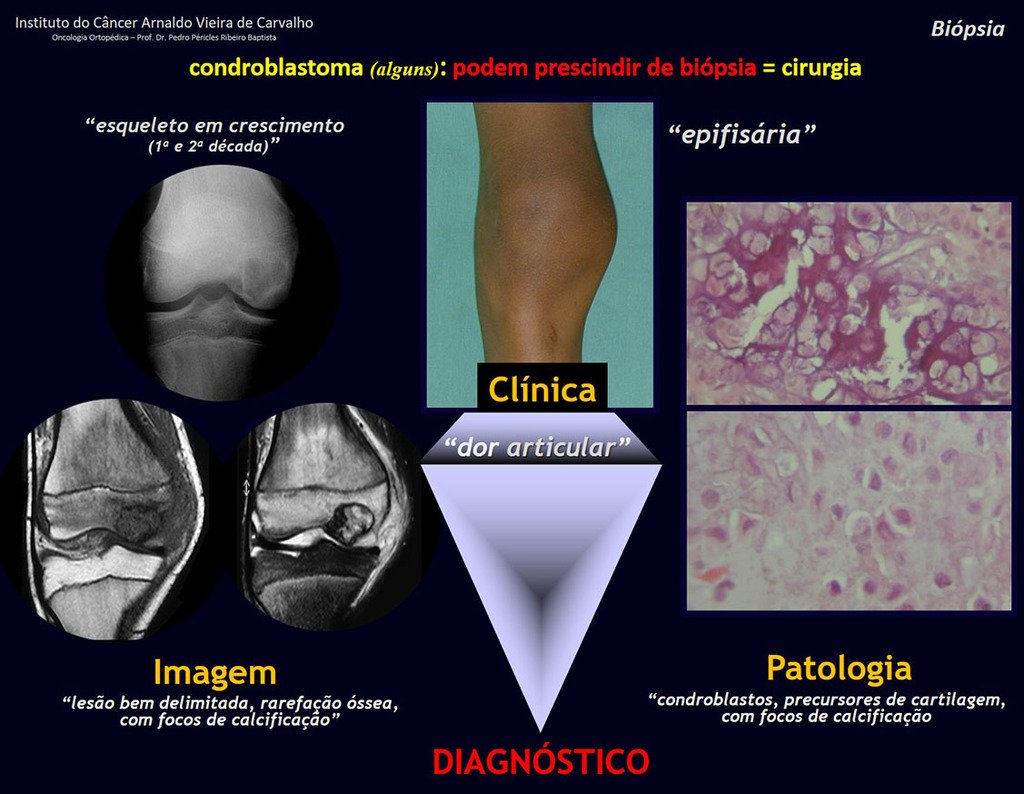

1 and . CHONDROBLASTOMA, figures 51 to 54.

IDENTITY: Benign epiphyseal neoplastic lesion of the growing skeleton (1st and 2nd decades ), characterized by bone rarefaction, erosion of the articular cartilage with inflation, cartilaginous cells (chondroblasts), giant cells and foci of calcification.

Adjuvant curettage and electrothermal surgery for this neoplasm, in these locations and in small-sized lesions, is nothing more than an incisional biopsy, in which the macroscopic appearance of cartilage allows complete curettage of the tumor. The presence of the pathologist in the surgery is useful to corroborate and assist the surgeon. Read: http://chondroblastoma

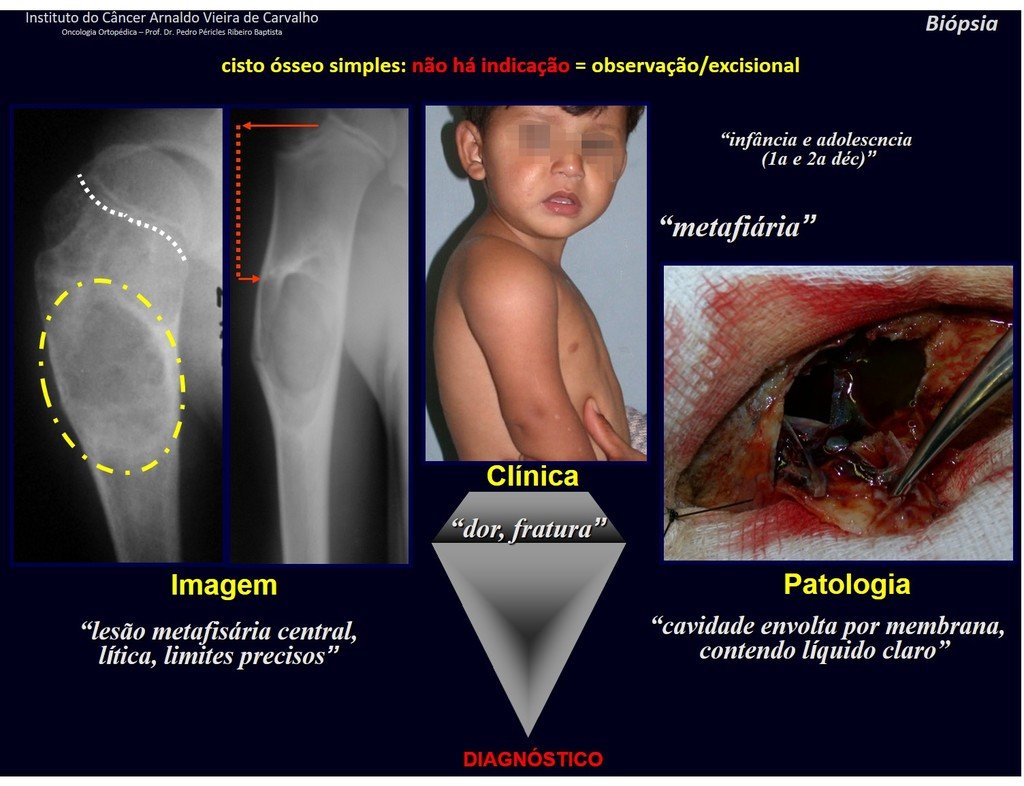

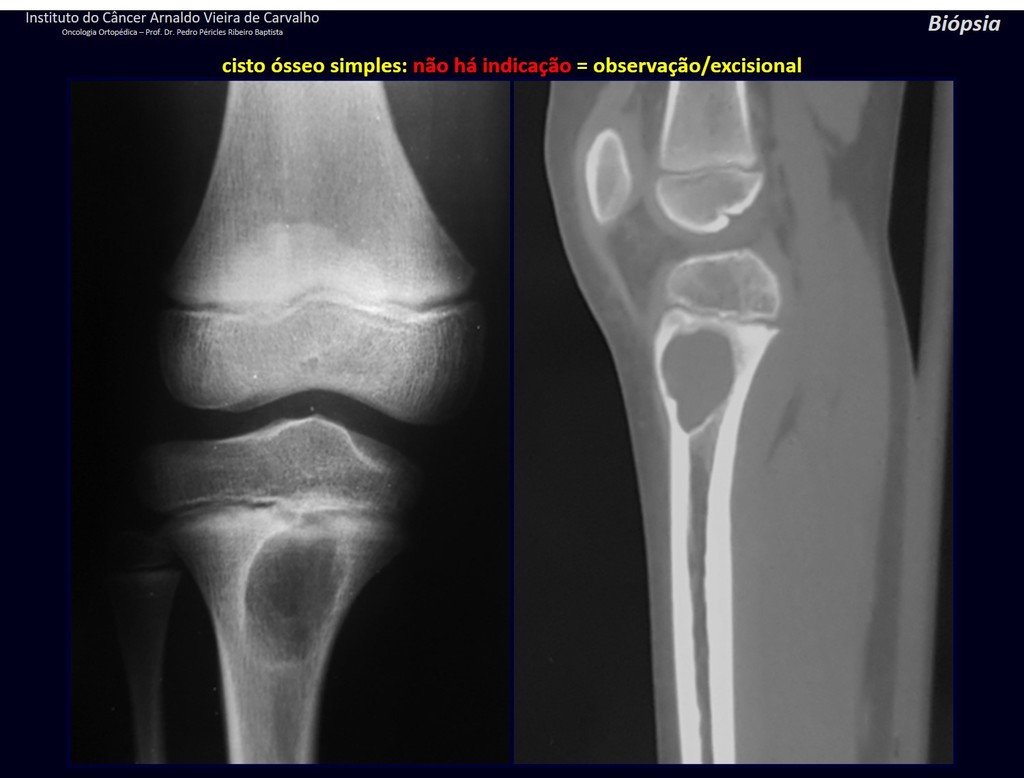

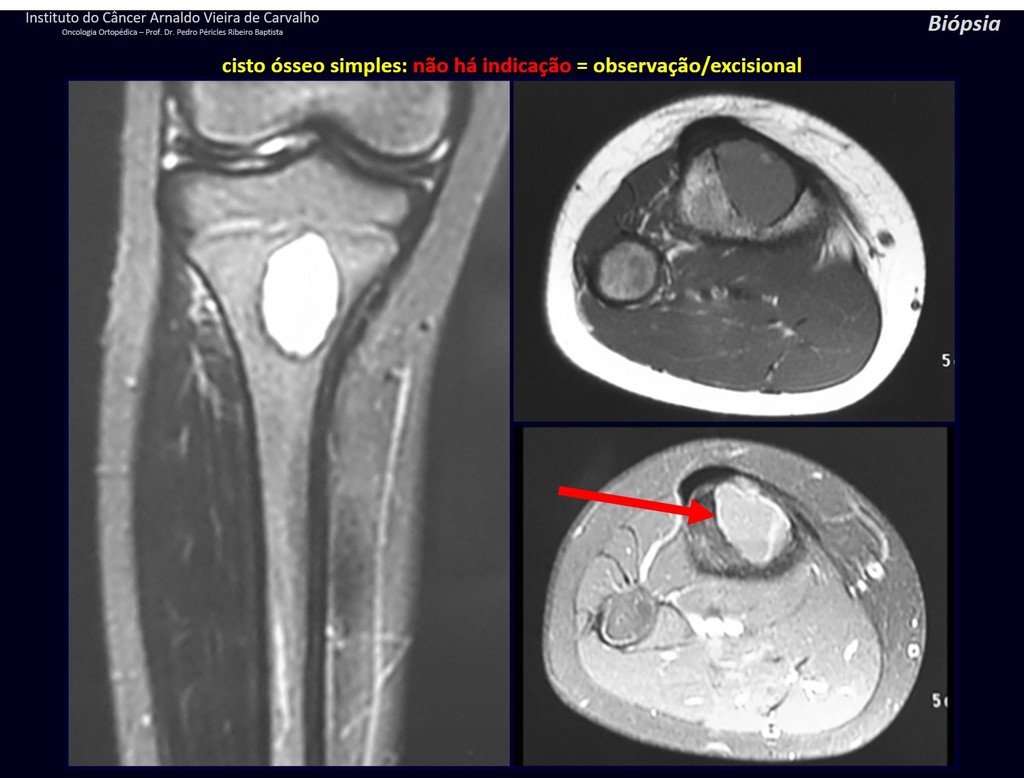

1f . SIMPLE BONE CYST – COS, figures 55 to 58.

IDENTITY: Pseudoneoplastic lesion, unicameral, surrounded by a membrane, well delimited, filled with serous fluid, central metaphyseal location , which does not exceed its width and occurs in children and adolescents.

Read: http://simple bone cyst

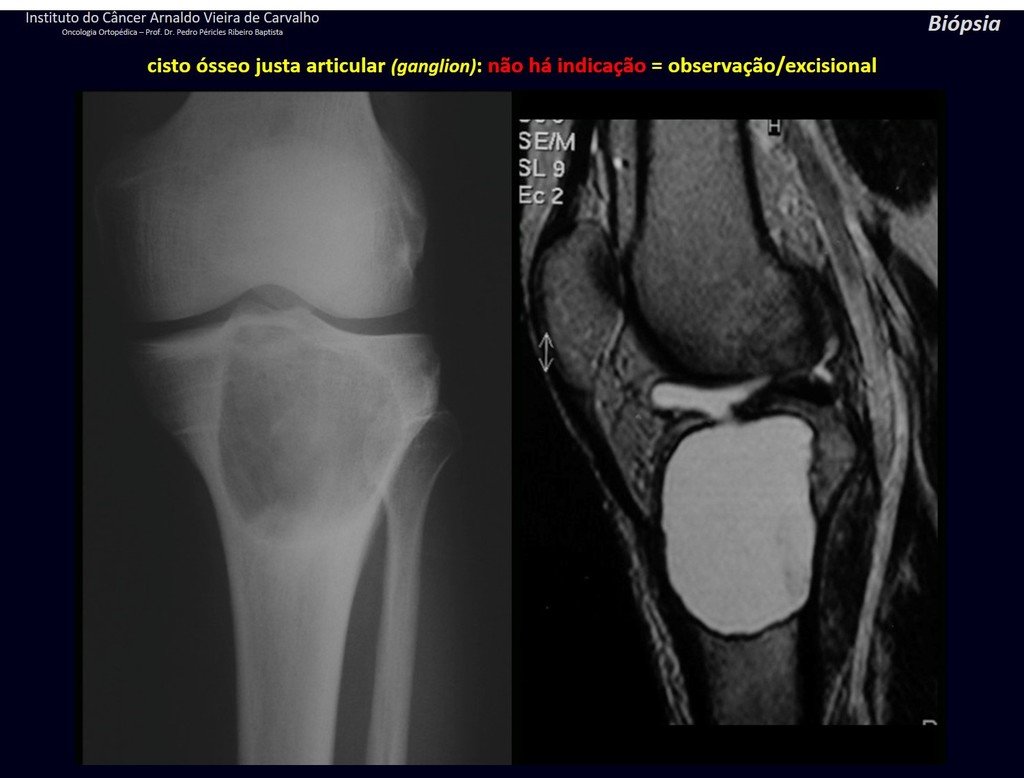

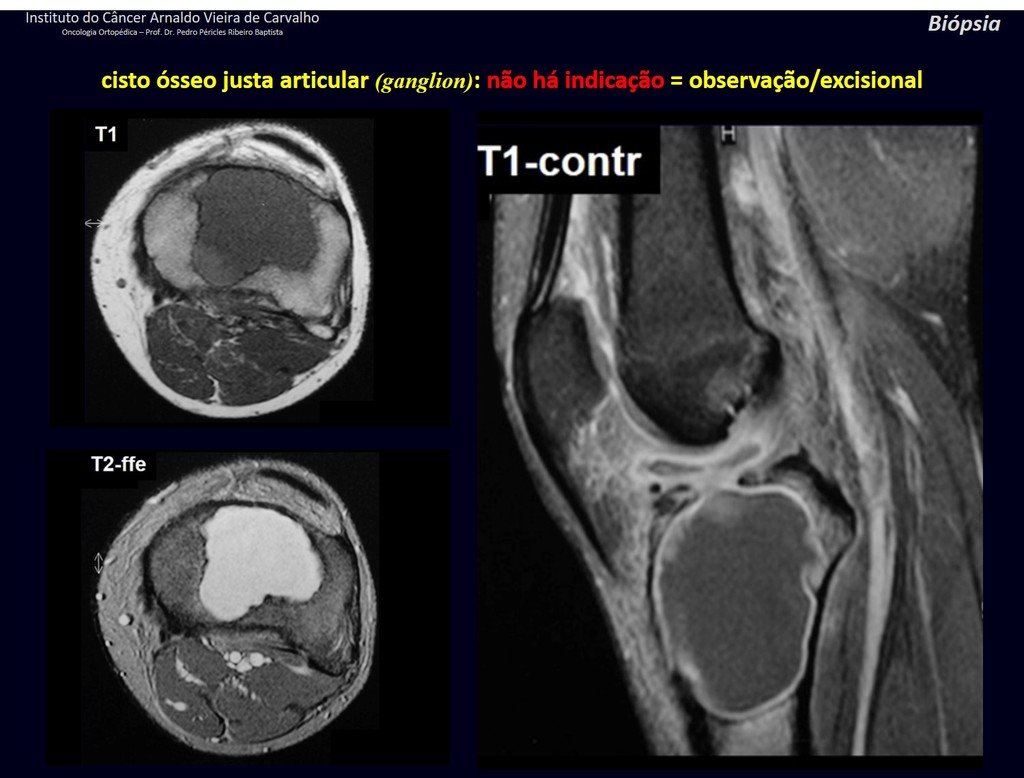

1g . JUSTAARTICULAR BONE CYST – GANGLION, figures 59 to 62.

IDENTITY: Pseudoneoplastic lesion, epiphyseal in location , unicameral, surrounded by synovial membrane, well defined and filled with serous fluid, which communicates with the adjacent joint.

These lesions do not require a biopsy for treatment.

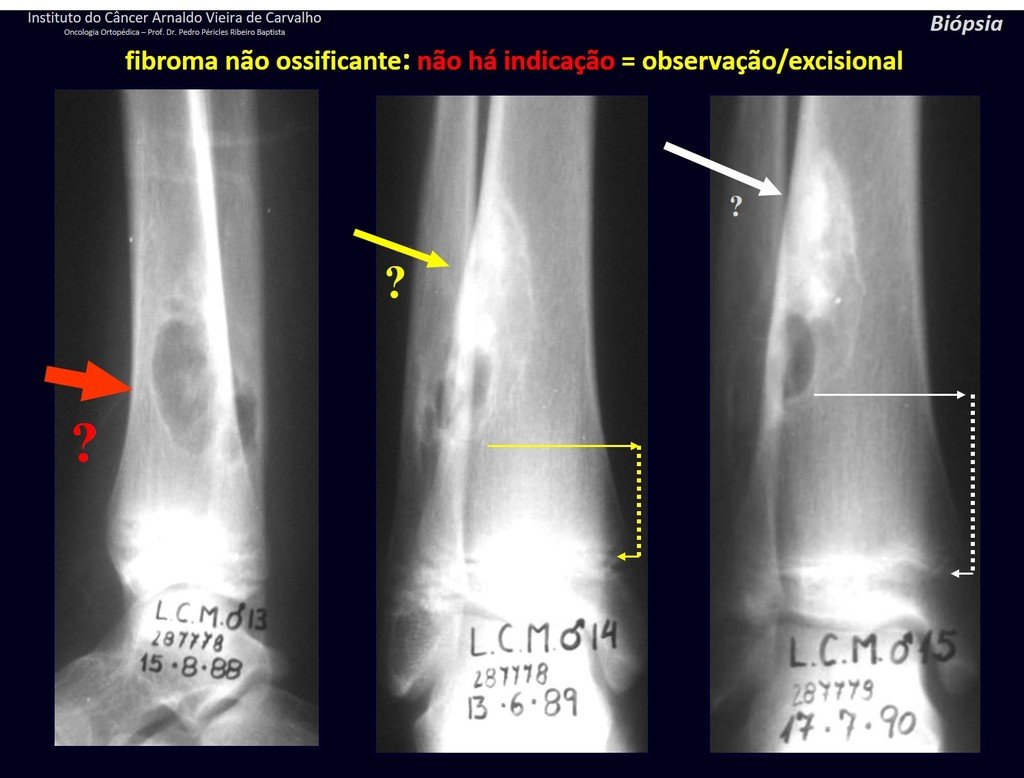

1h . CORTICAL FIBROUS DEFECT / NON-OSSIFYING FIBROMA, figures 63 and 64.

IDENTITY: Pseudoneoplastic lesion in the cortical bone with precise limits, asymptomatic. Occasional find.

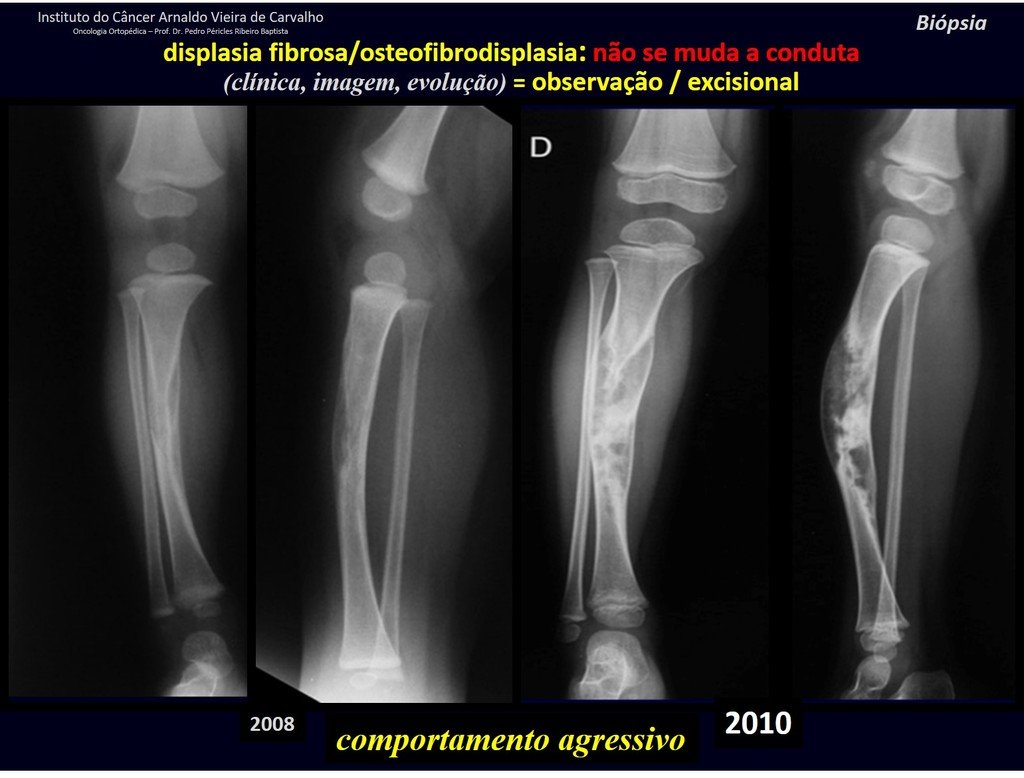

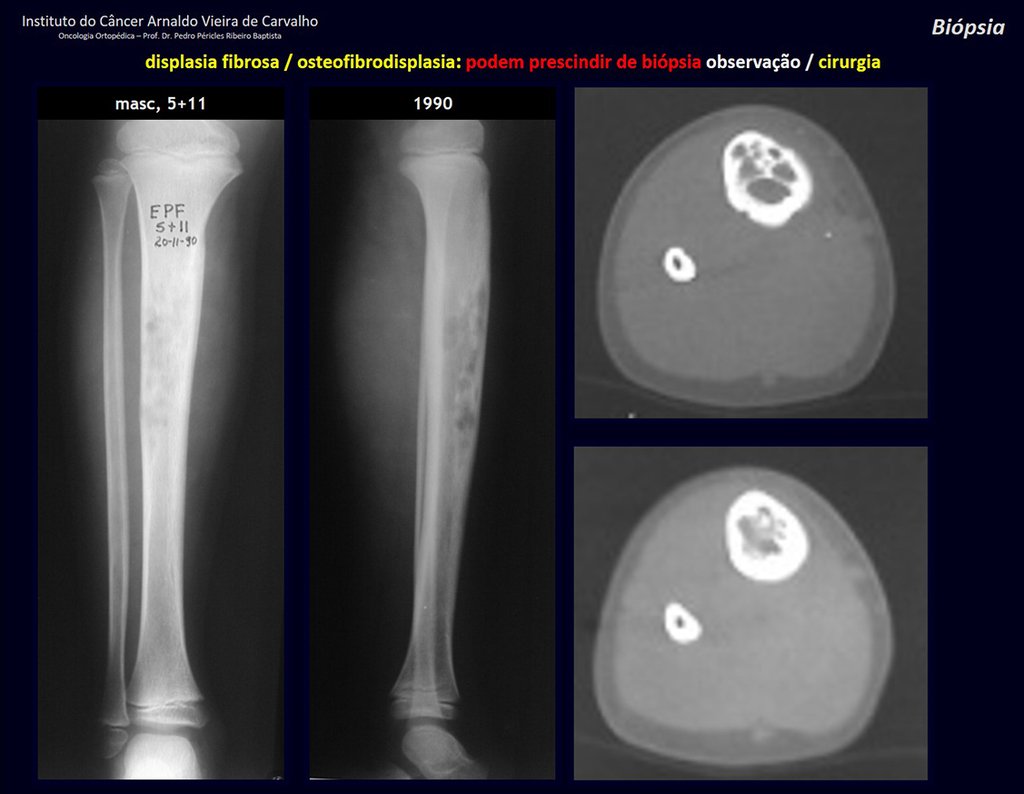

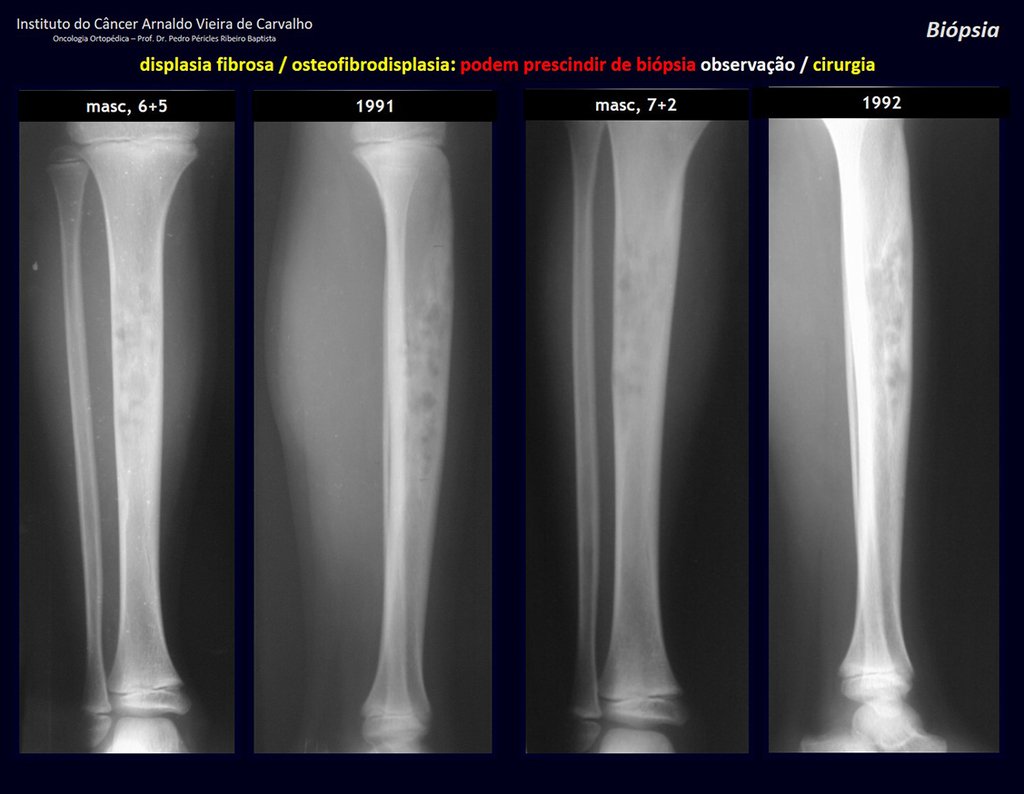

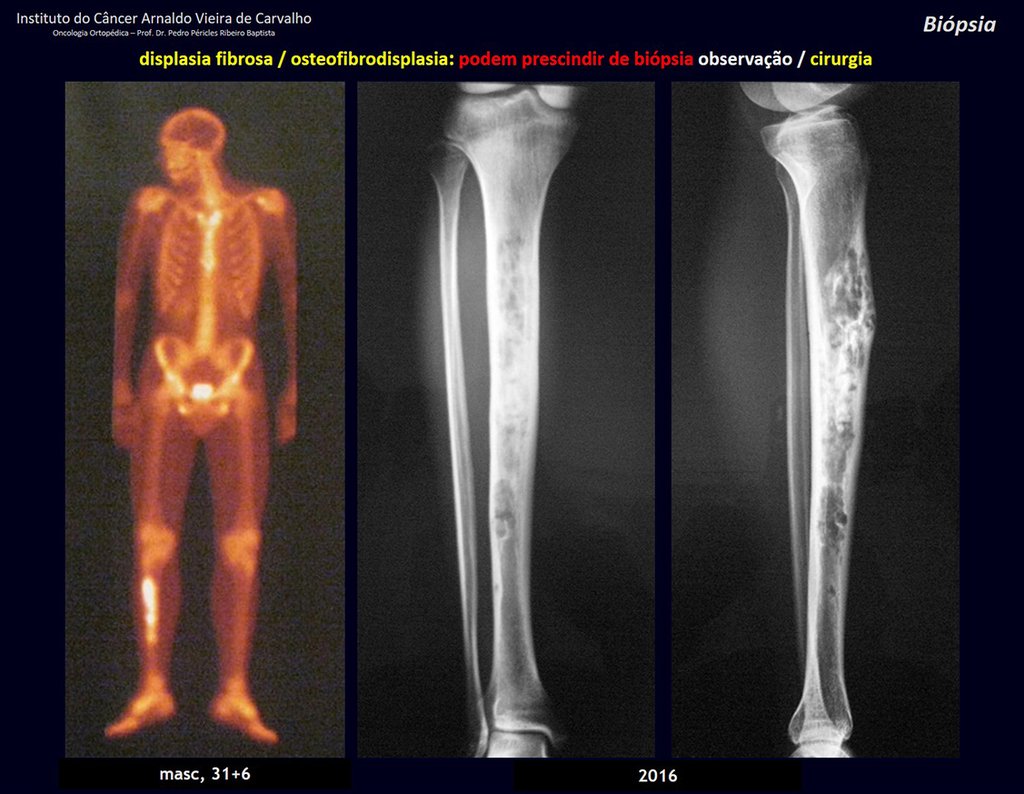

1i . FIBROUS DYSPLASIA OF THE TIBIA / OSTEOFIBRODYSPLASIA, figures 65 to 70.

IDENTITY: Pseudoneoplastic lesion in the tibial diaphysis with bone rarefaction of intermediate density, as if the bone had been “erased” , with a ground-glass appearance. It can occur in more than one location. Its evolution is variable and can cause deformity, dedifferentiation or harmonious growth, stabilizing at skeletal maturity.

1J . MYOSITIS OSSIFICANS, figures 71 and 72.

IDENTITY: Injury located close to a bone and in soft tissues, related to previous trauma, whose ossification begins in the periphery.

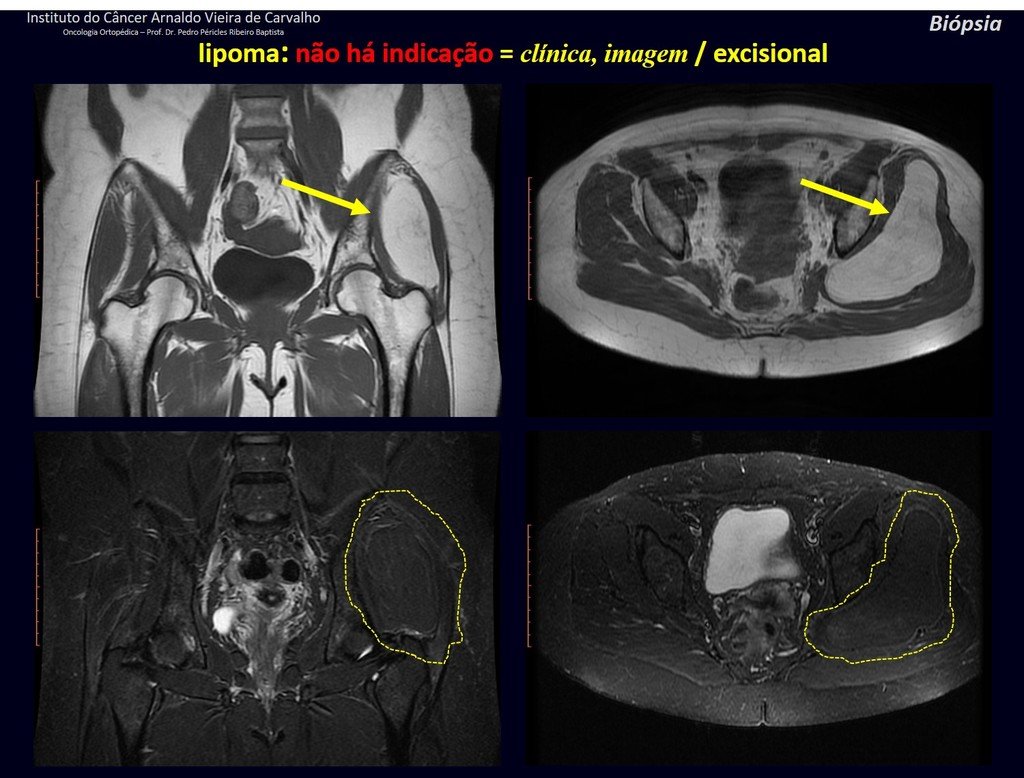

1k . SOFT TISSUE TUMOR – SOME , figures 73 to 78.

IDENTITY: Delimited, homogeneous lesions, with typical images, without contrast uptake or with uptake only in the periphery, can be operated on without prior biopsy, when the surgical approach would not be different, even in the case of a malignant neoplasm.

Malignant soft tissue tumors would have the same surgical resection procedure, with the narrow margins presented in the case above and would be complemented with local radiotherapy. Soft tissue sarcomas, to date, do not respond to chemotherapy nor show an improvement in the patient’s survival rate.

A possible biopsy could cause nerve damage and would not change the management.

Biopsy can be performed, it is academic, it complements the case studies, but surgical resection must prevail, even in the case of malignant neoplasia. Soft tissue sarcomas, to date, do not benefit from neoadjuvant treatment and ablative surgery does not alter survival.

GROUPS 3 : Biopsy is necessary for treatment (surgery; with/without neoadjuvance)

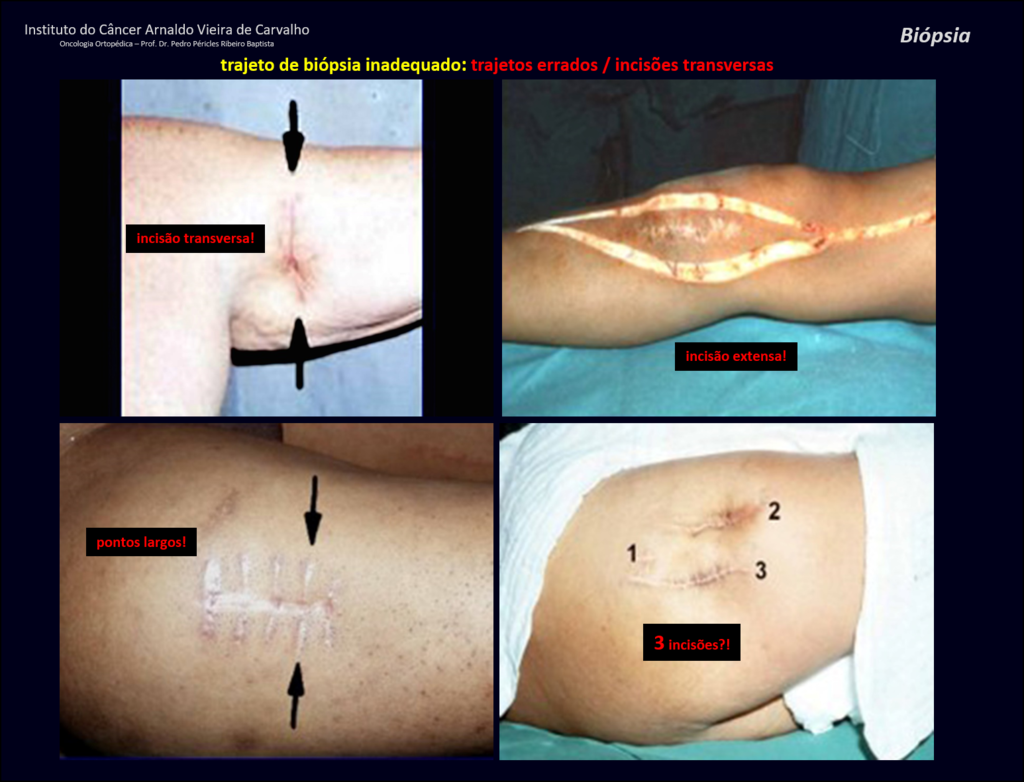

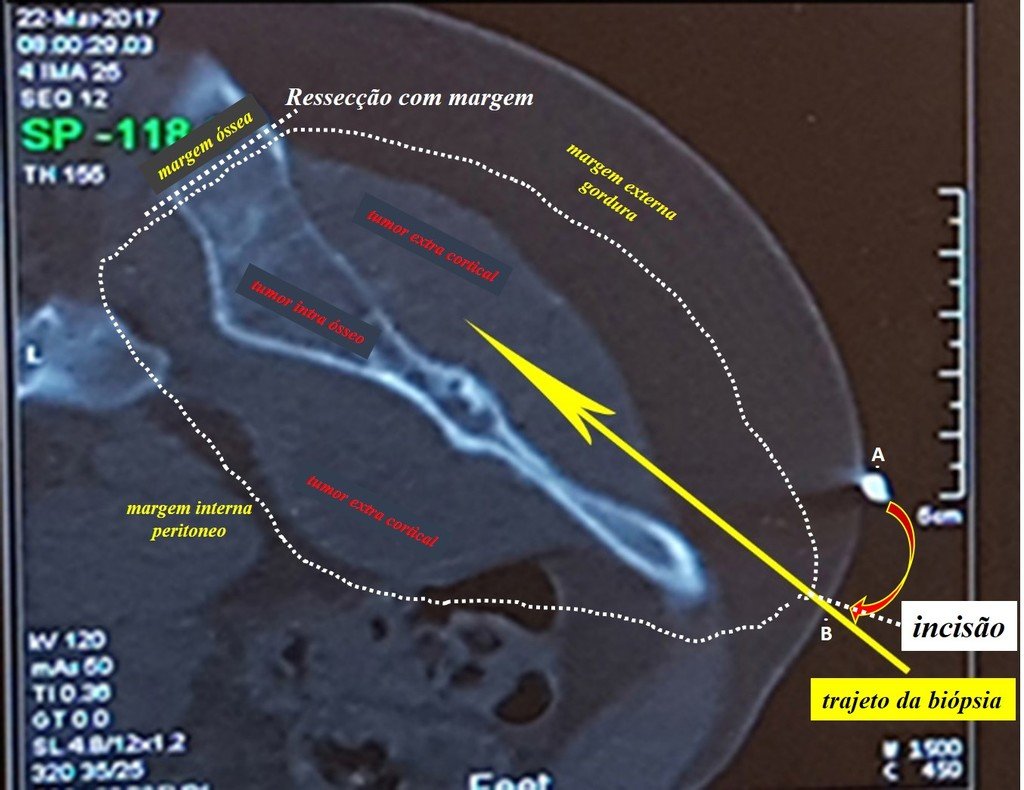

We need to emphasize that the biopsy must be performed/ monitored by the surgeon who will perform the surgery. Your presence is essential for this to be carried out in accordance with the surgery planning.

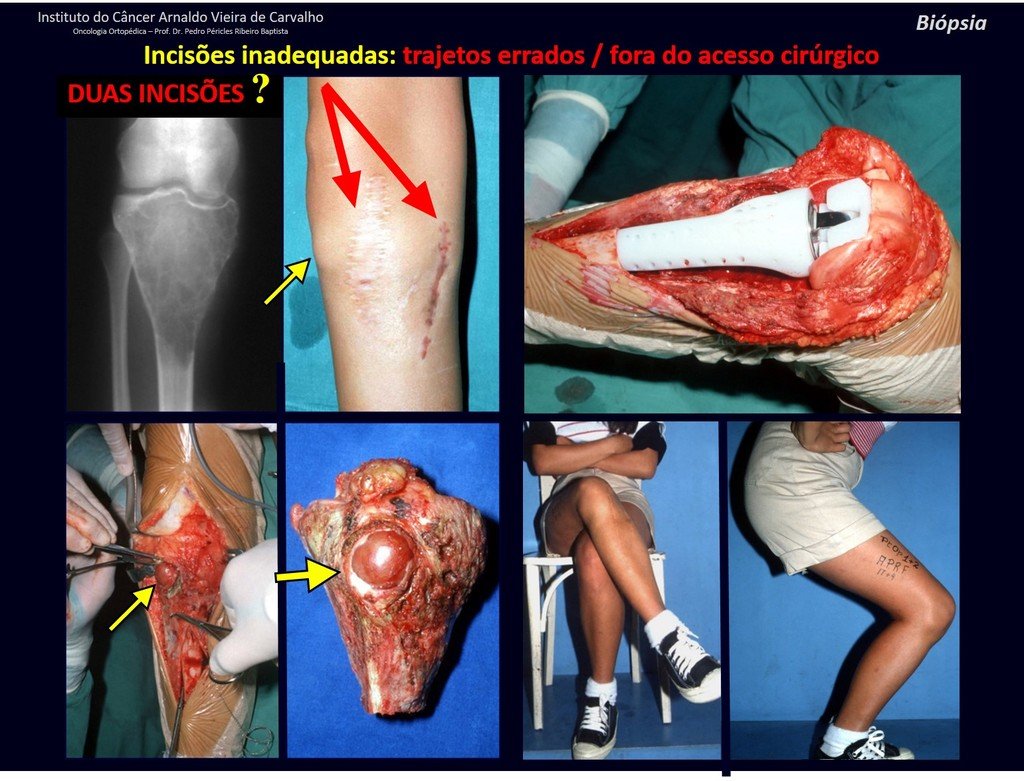

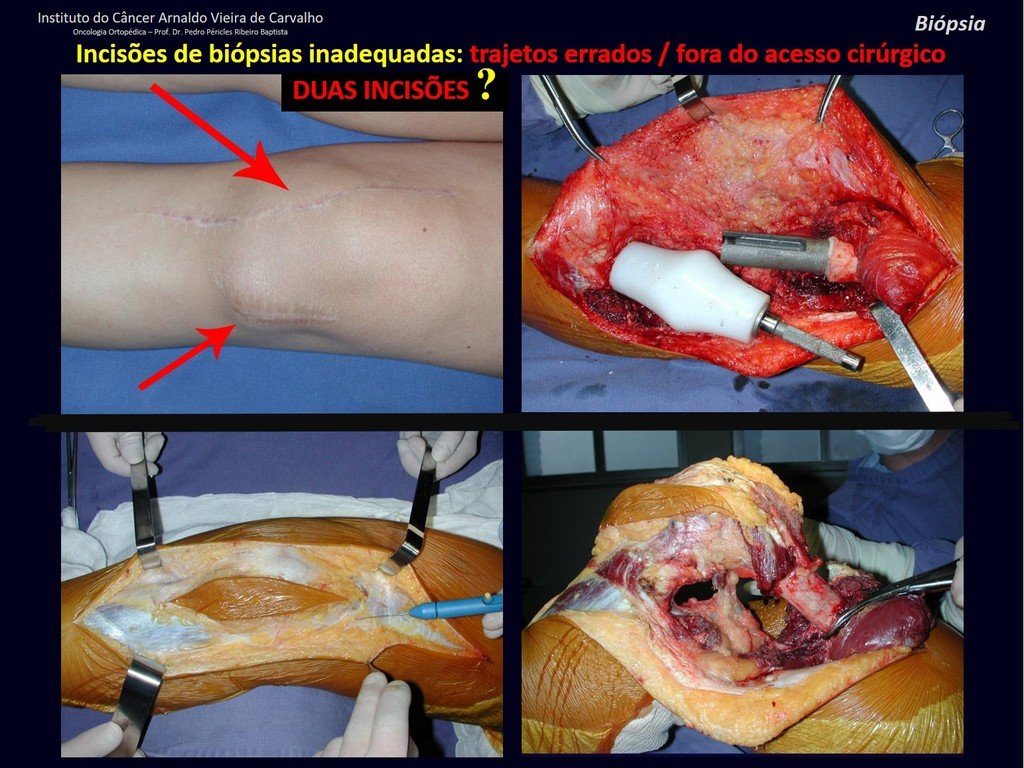

Transverse incisions should not be made, nor extensive incisions where there is no musculature for subsequent coverage, such as on the leg, for example. The suture should not have points far from the incision, as this will require a larger resection of tissue and much less more than one incision, figures 79 (tables A, B, C and D) and 80.

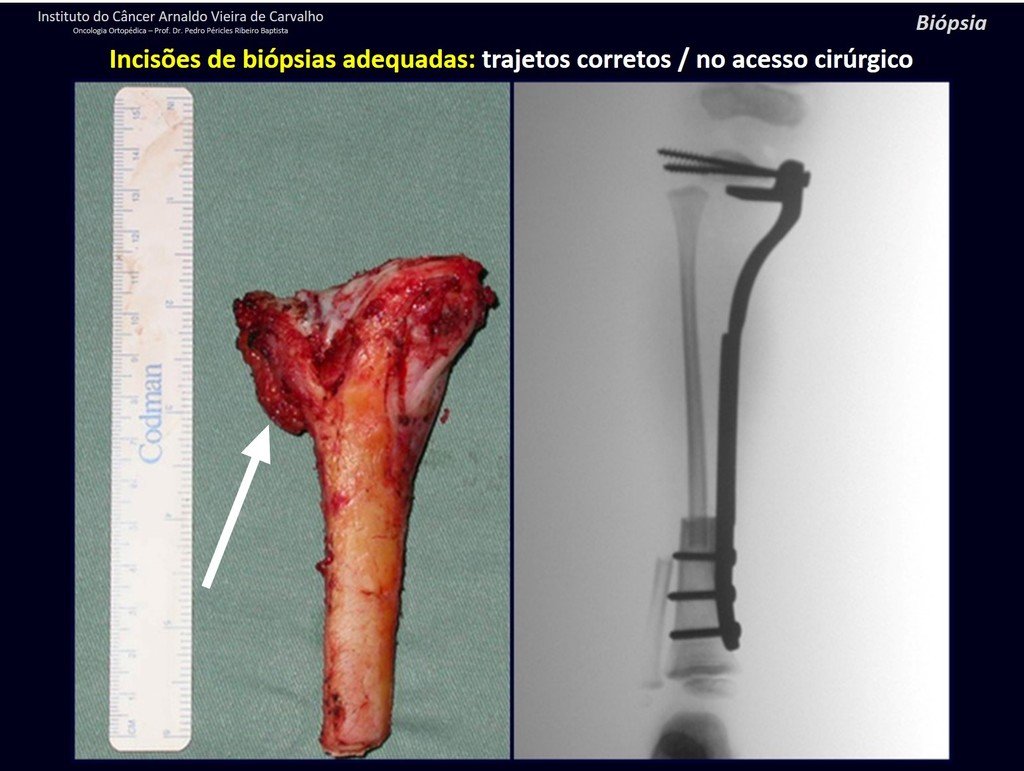

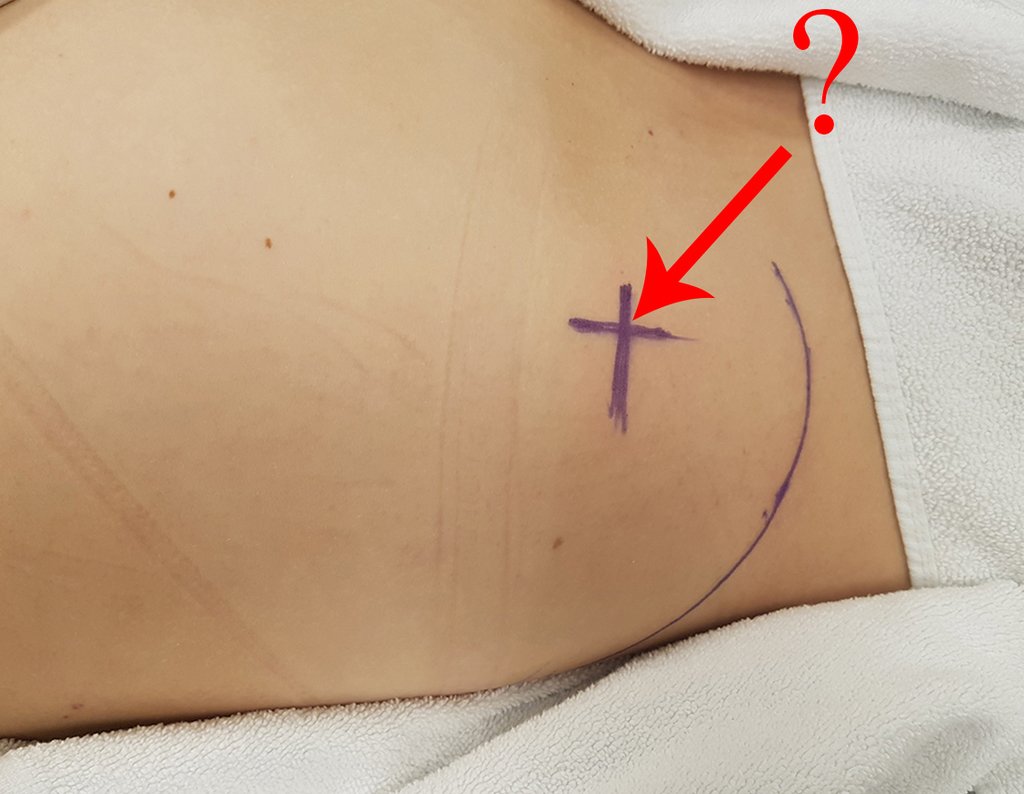

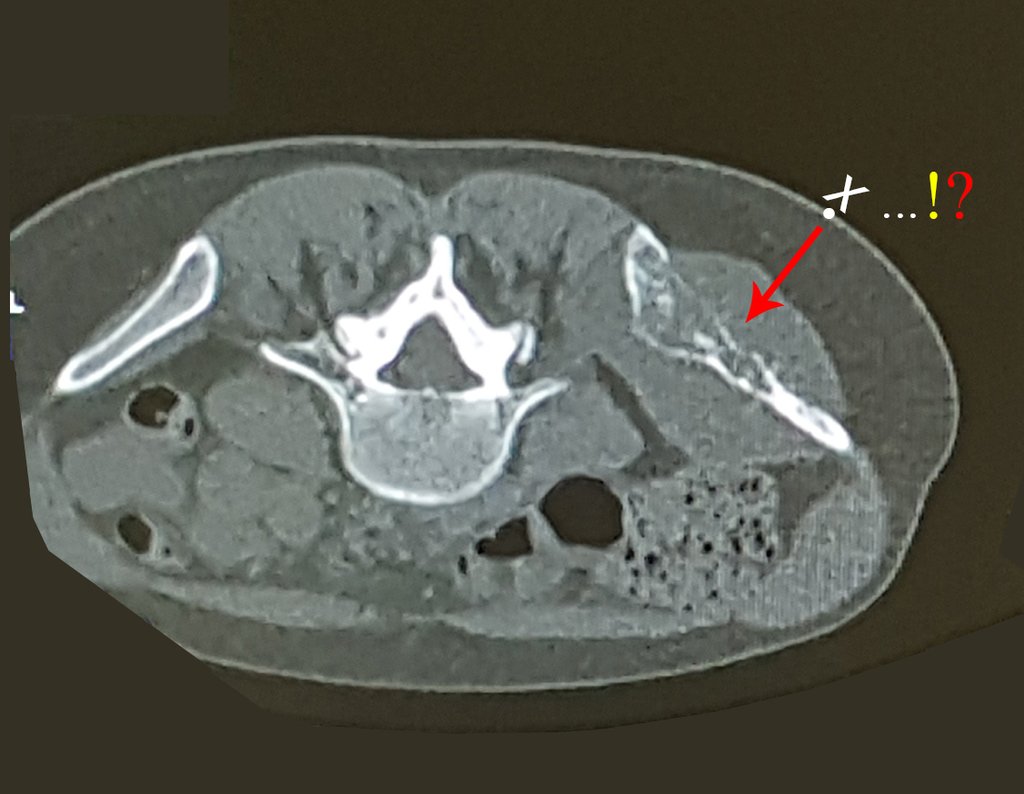

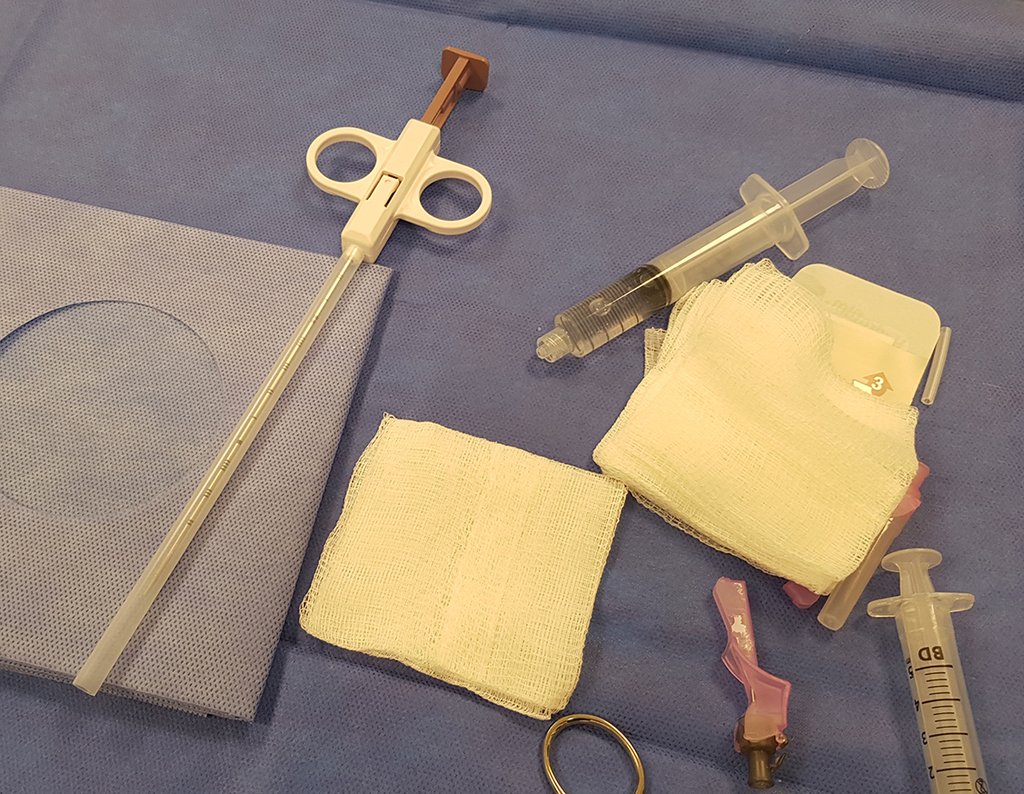

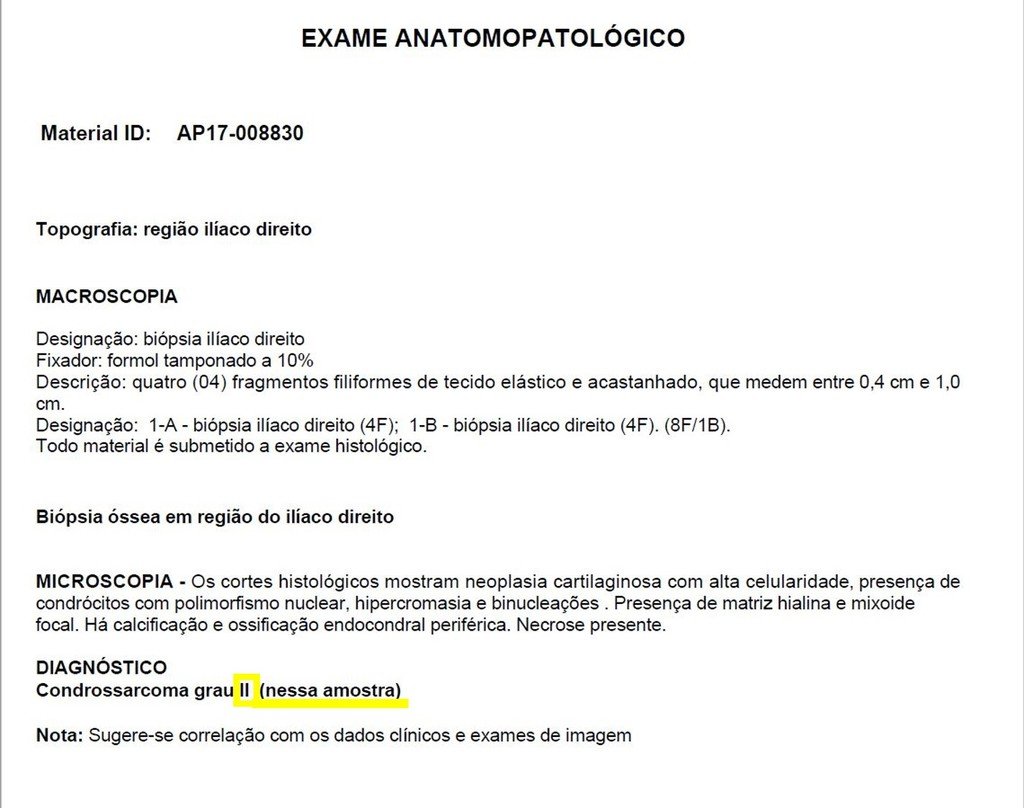

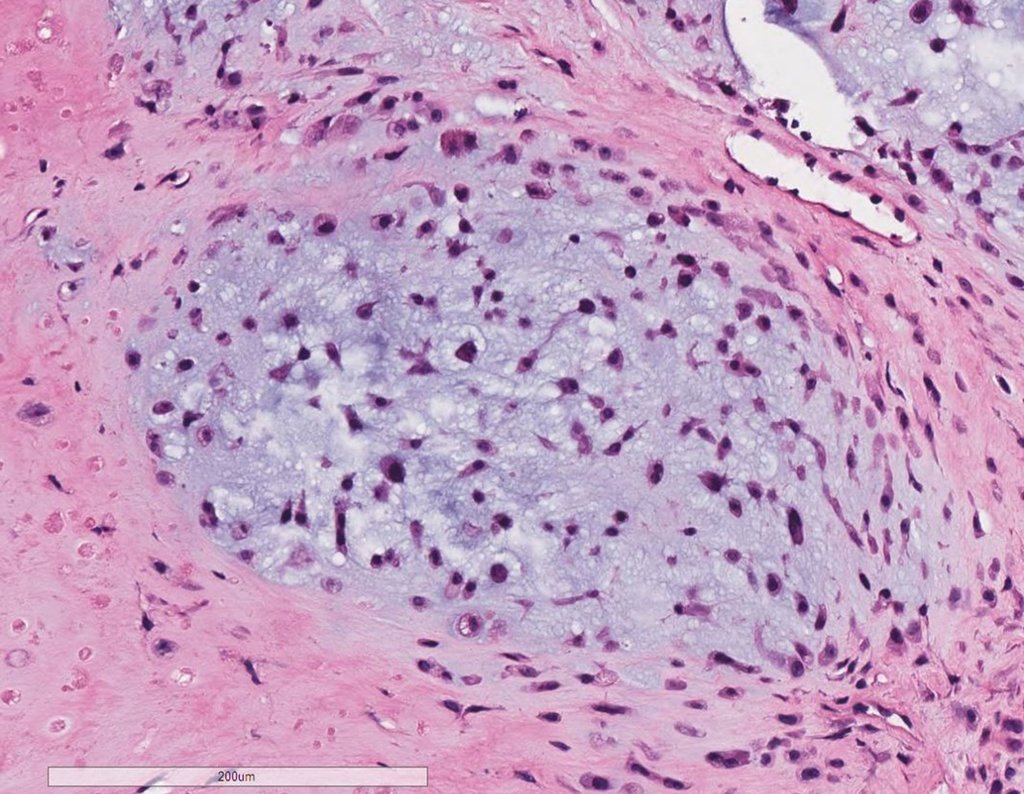

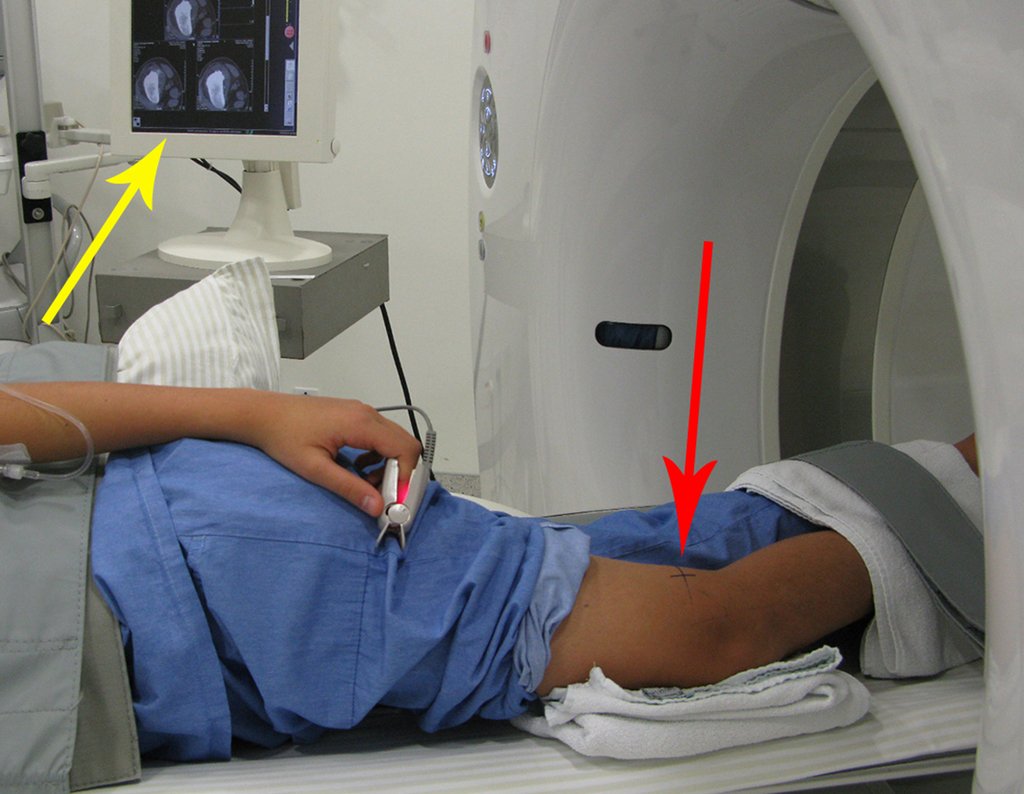

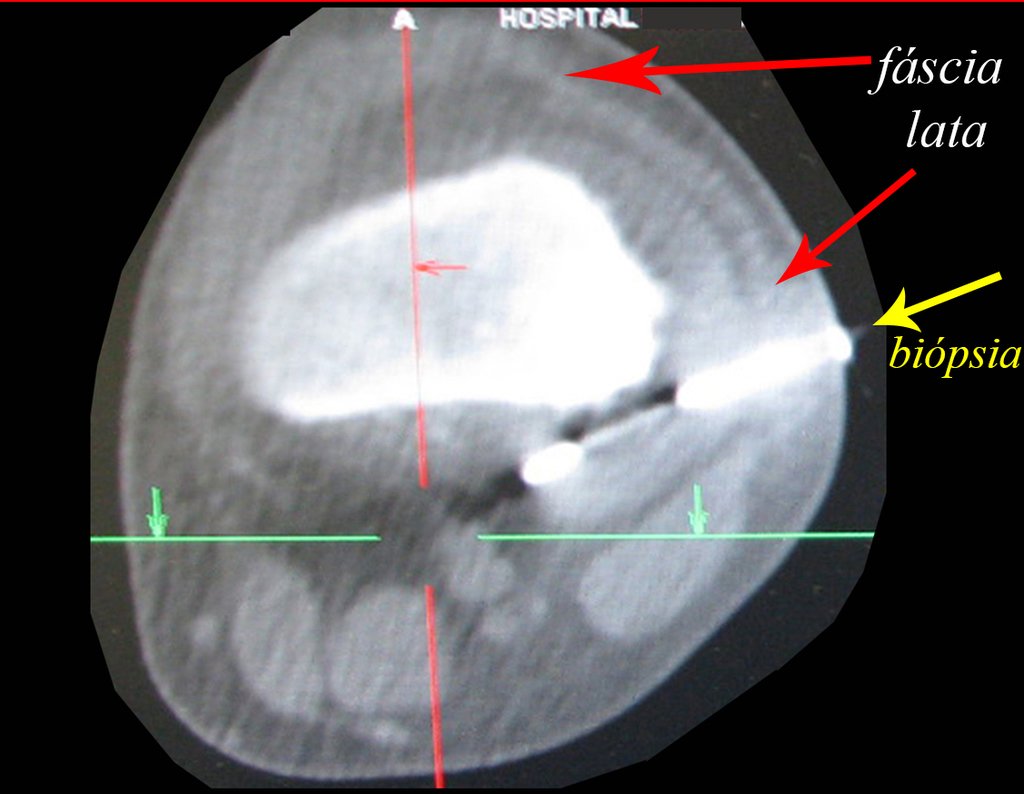

Below, we exemplify two cases of biopsies performed correctly, figures 83 to 86.

The Rx operator argued that that position was the best and that we could easily obtain the material for the histological study and… made an X where he would obtain the sample! Figures 95 and 96.

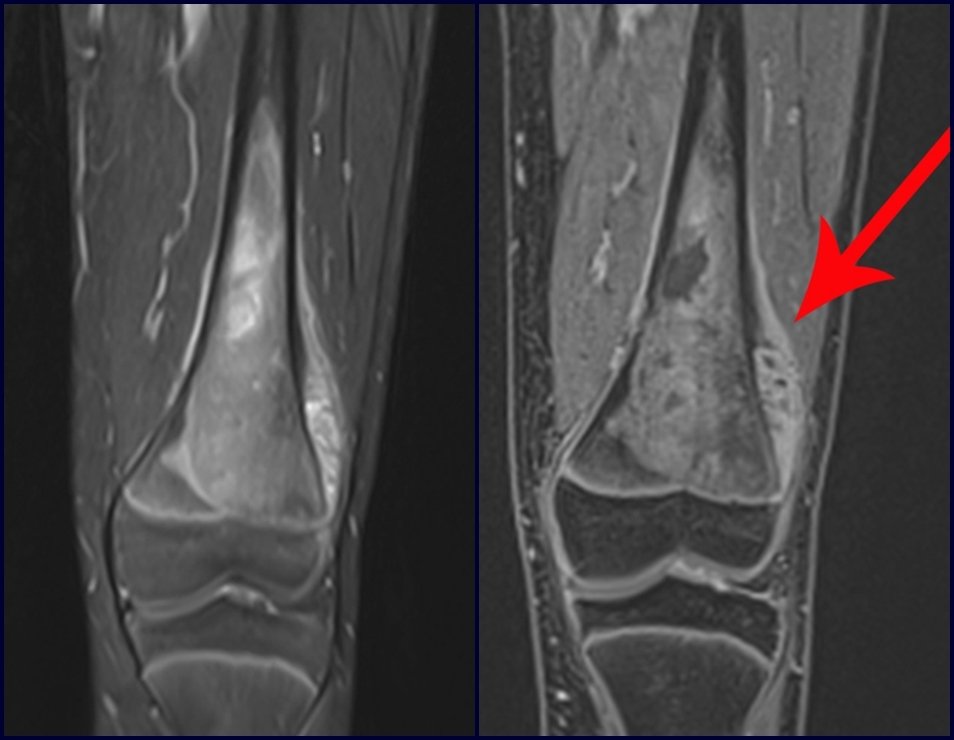

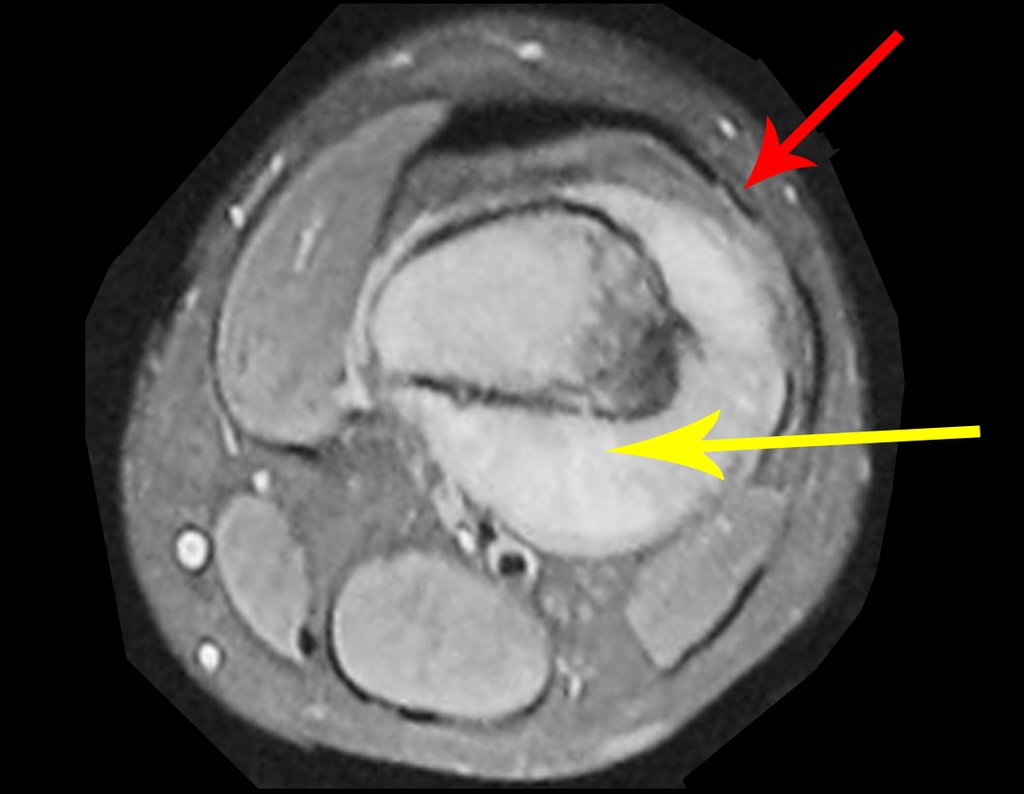

We very frequently see patients with biopsy scars performed in the anterolateral region of the distal metaphysis of the femur. The red arrow points to the fascia lata, which is most often interrupted by the biopsy path, carried out by professionals who will not operate on the patient, making it difficult to cover future surgery and the function of this limb that will need to be reconstructed.

The yellow arrow indicates the posterolateral path, most suitable for biopsy and reconstruction, providing the best coverage and function.

To perform the biopsy using this route, the appropriate positioning of the patient is in the prone position, figures 119 to 122.

For the treatment of tumors of the distal end of the femur, such as this lesion, with this degree of involvement and location, we recommend biopsy as described and neoadjuvant induction chemotherapy, resection with oncological margin and reconstruction with modular prosthesis and adjuvant chemotherapy.

The patient in this example is out of treatment, with excellent function, and the complete case can be seen at Link: http://osteosarcoma-length discrepancy .

The performance of musculoskeletal biopsy, aiming at the diagnosis and adequate treatment of neoplasms, must be very well planned and carried out by experienced professionals.

“Carrying out musculoskeletal biopsies, aiming at the diagnosis and adequate treatment of neoplasms, must be very well planned and carried out by experienced professionals and with the participation of the surgeon who will be managing the case”.

Author: Prof. Dr. Pedro Péricles Ribeiro Baptista

Orthopedic Oncosurgery at the Dr. Arnaldo Vieira de Carvalho Cancer Institute

Office : Rua General Jardim, 846 – Cj 41 – Cep: 01223-010 Higienópolis São Paulo – SP

Phone: +55 11 3231-4638 Cell:+55 11 99863-5577 Email: drpprb@gmail.com