Check out the video of the lecture

Total sacrectomy technique using Gigli saws Part II

In this second part of the total sacrectomy technique using Gigli saws, we will demonstrate its evolution, highlighting the use of laparoscopy. We will discuss its application for guiding the Gigli saws from the pelvic cavity to the dorsal region of the patient.

The first time we used laparoscopy was in a case involving a patient with an osteolytic lesion in the S-3 sacral foramen.

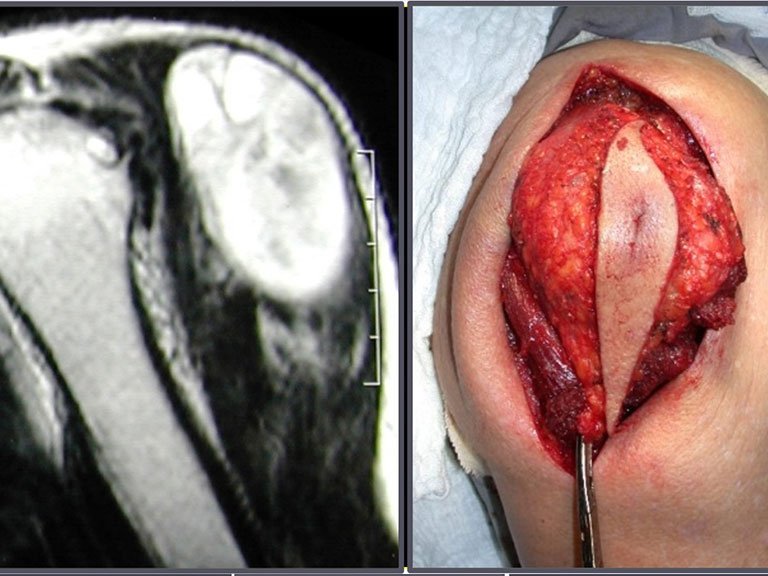

She presented with clinical symptoms of pain and numbness in her left leg. The X-ray revealed an enlarged foramen in the S-3 sacral vertebra. The CT scan showed a well-defined area, and the MRI exhibited a circumscribed lesion, bounded by a thick pseudocapsule. In the sagittal section, we observed the formation of a sacral tumor and its continuity with the nerve root, suggesting it was a schwannoma. An arteriography was performed for further study. The CT reconstruction indicated that the lesion was likely slow-growing, chronic, and benign.

A surgeon performed the laparoscopy, opening the retroperitoneum and isolating the iliac vessels under our guidance, to ligate and cut the left internal iliac artery and vein. Then, the tumor was exposed, and we confirmed its continuity with the S-3 root, resembling a horse’s tail. Next, he placed the tumor inside a surgical glove and aspirated the contents, removing everything through the laparoscopic tube. The patient was able to walk on the second day after surgery.

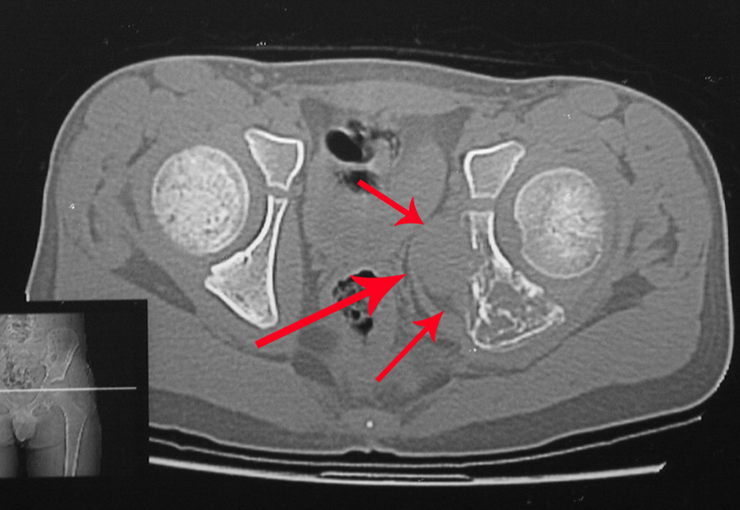

We discussed the possibility of performing the dissection of sacral tumors by passing the Gigli saws laparoscopically. To acquire the learning curve, we started with a case of Ewing’s sarcoma affecting the sacrum below S-3. In this case, we only needed to pass one saw horizontally. The tumor was successfully resected oncologically.

A Kirschner wire is placed as a guide, and we position two segments of the tube: the first is shorter and will exit through the patient’s back, while the second will push the first and be removed first, as per the diagram. We repeated this operation for the passage of the other saws. This way, we have the three saws safely positioned to make the osteotomies through the posterior approach. Currently, we use laparoscopy to perform all the procedures that were previously done through the anterior approach.

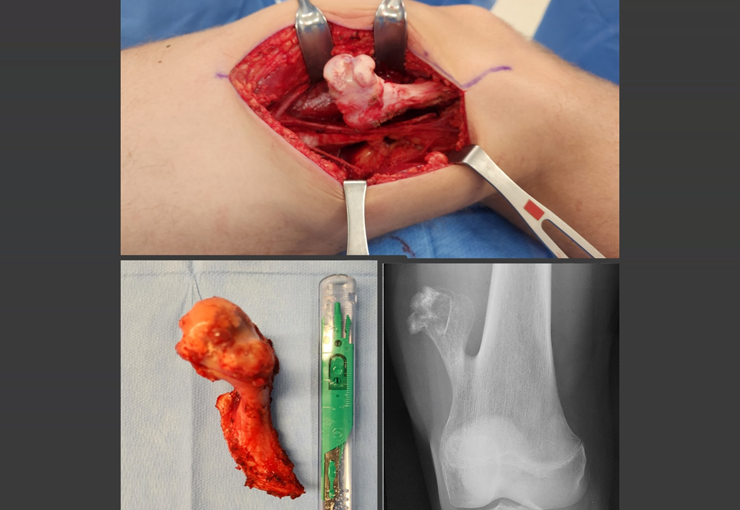

The case of a patient with a large volume chordoma, involving the entire sacrum and with difficulty in defecating and urinating, who had been bedridden for eight months in another hospital, was decisive in the approval of this technique. The patient had pressure ulcers and a posture of hip and knee flexion. She was operated on using the Gigli saw technique, positioned laparoscopically, and then we performed the release and lengthening of the hip and knee flexors, realigning the lower limbs. This chordoma case, despite its severity, was successfully operated on, and the total sacrectomy with laparoscopic assistance was successful. The patient started physiotherapy and rehabilitation of bladder and bowel excretory functions through abdominal maneuvers. She can walk with the aid of a walker and is reintegrated into daily life, independently, despite motor deficits in the ankle dorsiflexor muscles.

Sacrectomy with laparoscopic assistance is advantageous, presenting shorter surgery times, reduced need for blood transfusions, and satisfactory functional outcomes. Currently, we see no need to perform reconstructions.